Scientists prevent heart failure in mice

Two small RNA molecules play a key role in the growth of heart muscle cells

Cardiac stress, for example a heart attack or high blood pressure, frequently leads to pathological heart growth and subsequently to heart failure. Two tiny RNA molecules play a key role in this detrimental development in mice, as researchers at the Hannover Medical School and the Göttingen Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry have now discovered. When they inhibited one of those two specific molecules, they were able to protect the rodent against pathological heart growth and failure. With these findings, the scientists hope to be able to develop therapeutic approaches that can protect humans against heart failure.

Respiratory distress, fatigue, and attenuated performance are symptoms that can accompany heart failure. Germany-wide approximately 1.8 million people suffer from this disease. A reason for this can be an enlarged heart, a so-called cardiac hypertrophy. It may develop when the heart is subjected to permanent stress, for example, due to persistent high blood pressure or a valvular heart defect. In order to boost the pumping performance, the heart muscle cells enlarge – a condition that frequently results in heart failure if not treated.

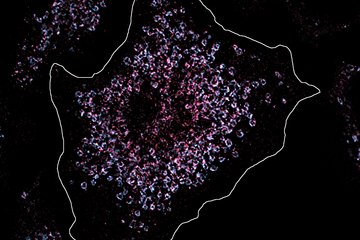

A research team at the Göttingen Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry and the Hannover Medical School discovered that two small RNA molecules play a key role in the growth of heart muscle cells: the microRNAs miR-212 and miR-132.

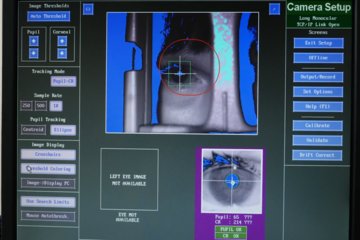

The scientists had observed that these microRNAs are more prevalent in the cardiac muscle cells of mice suffering from cardiac hypertrophy. To determine the role that the two microRNAs play, the scientists bred genetically modified mice that had an abnormally large number of these molecules in their heart muscle cells. "These rodents developed cardiac hypertrophy and lived for only three to six months, whereas their healthy conspecifics had a normal healthy life-span of several years," explained Kamal Chowdhury, researcher in the Department of Molecular Cell Biology at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry. "For comparison, we also selectively switched off these microRNAs in other mice. These animals had a slightly smaller heart than their healthy conspecifics, but did not differ from them in behaviour or life-span," continued the biologist. The crucial point is when the scientists subjected the hearts of these mice to stress by narrowing the aorta, the mice did not develop cardiac hypertrophy – in contrast to normal mice.

The scientists were also able to protect normal mice against the disease. When they gave them a substance that selectively inhibits microRNA-132, no pathological cardiac growth occurred – even when the hearts of these mice were subjected to stress. "Thus, for the first time ever, we have found a molecular approach for treating pathological cardiac growth and heart failure in mice," said the cardiologist Thomas Thum, MD, Director of the Institute for Molecular and Translational Therapy Strategies (IMTTS) at the Hannover Medical School. With these findings, the researchers hope that they will be able to develop therapeutic approaches that can also protect humans against heart failure. "Such microRNA inhibitors, alone or in combination with conventional treatments, could represent a promising new therapeutic approach," said Thum.

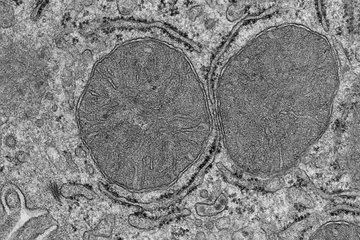

"In mice with an overdosage of the two microRNAs in their heart muscle cells, the cellular ‘recycling program' is curbed," explained Ahmet Ucar, who together with Shashi K. Gupta was responsible for the experiments. In this recycling process, the cell breaks down components that are damaged or no longer required and reuses their constituents – a vital process that, for example, ensures the organism’s survival under stress conditions. In mice without the microRNAs -212 and 132, this recycling program is more active than in their normal conspecifics. Conceivably, the reduced cellular recycling could be a cause of the observed cardiac hypertrophy.

(VK)