Mapping the stress axis in detail

Uncovering the activities of the organs, tissues and cells responsible for the body’s stress response revealed new cells and possible new drug targets

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Germany and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel made use of new scientific technology to investigate the so-called stress axis that runs from the brain down to the adrenal glands. In particular, they uncovered numerous changes that occur in single cells along this axis as chronic stress continually prompts the adrenals to secrete the stress hormone, cortisol, and they found a new subpopulation of cells that aids and abets the stress response in these glands. Their findings may be relevant to a number of stress-related diseases from anxiety and depression to metabolic syndrome and diabetes.

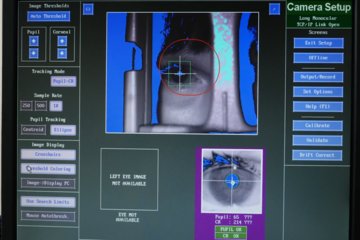

The three main components of the stress response axis are the hypothalamus in the brain, the pituitary right next to the brain and the adrenal glands near the kidneys. The message is relayed along this axis from the hypothalamus through the pituitary to the adrenals, which then release cortisol through the blood to the rest of the body, initiating the physical and behavioral symptoms of tension and stress – from tightening of the jaw to upset stomachs and trembling.

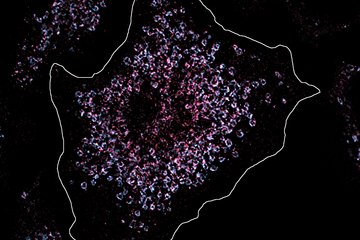

The new study, led by postdoctoral fellow Juan Pablo Lopez in the joint neurobiology lab of Alon Chen in the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry and the Weizmann Institute of Science, made use of a technique that allows researchers to identify differences across all cell types in a tissue. This method is something like identifying the individual fruits in a bowl of fruit salad – rather than the standard methods of creating a “smoothie” and then trying to identify the average characteristics of all the fruits together. But in this case, the “fruit salad” was much more complex than separating the apples from oranges: Pablo Lopez and the team mapped the entire length of the stress axis, checking the activities of single cells all along the route. And they conducted this analysis on two sets of mice – one unstressed and one exposed to chronic stress.

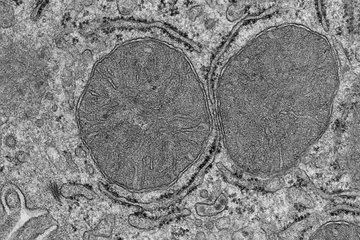

All in all, the team mapped 21,723 cells along the three points in that axis, and they compared their findings from the two sets of mice. They noted that as the stress message moved from one organ to the next, the gene expression in the cells and the tissues themselves underwent greater changes. The team found 66 genes that were altered between normal and stressed mice in the hypothalamus, 692 in the pituitaries and a whopping 922 in the adrenals. The adrenals are glands that can change their size visibly under chronic stress exposure, and it was here that the researchers noted the most significant alterations among the various cells.

The unprecedented resolution of the technique enabled the researchers to identify, for the first time, a subpopulation of adrenal cells that may play a crucial role in the stress response and adaptation. These were endocrine cells sitting in the outer layer, or adrenal cortex. Among other things, the team identified a gene, known as Abcb1b, and found it to be overexpressed in these cells under stress situations. This gene encodes a pump in the cell membrane that expels substances from the cell, and the scientists think it plays a role in the release of cortisol. “If extra stress hormones are created, the cell needs extra release valves to let those hormones go,” says Pablo Lopez.

Are the findings in mice relevant to humans?

In collaboration with researchers in university-based hospitals in the UK, Germany, Switzerland and the US, the scientists obtained adrenal glands that had been removed from patients to relieve the symptoms of Cushing’s disease. Though the disease is the result of a growth on the pituitary, the result can be identical to chronic stress – weight gain and metabolic syndrome, high blood pressure and depression or irritability – so in some cases it is treated by removing the adrenal glands, that is, the source of the stress hormone. Indeed, the cells in these patients’ adrenals presented a similar picture to those of the mice in the chronic stress group.

The gene Abcb1 was known to the researchers from previous studies into the genetics of depression. It had been found that this gene is polymorphic – it has several variants – and that at least one version is tied to antidepressant treatment response. The group analyzed the expression of this variant in blood tests taken from a group of subjects who suffer from depression and who were subjected to temporary stress. As in treatment response, it seemed that different versions of the gene play a role in the range of coping abilities of the adrenal glands for dealing with stress signals coming down the axis.

Chronic stress, of course, can ultimately affect every part of the body and open the door to numerous health issues. The new study, because it looks at the entire axis, on the one hand, and has mapped it down to the gene expression pattern of its individual cells, on the other, should provide a wealth of new information and insight into the mechanisms behind the stress axis. “Most research in this field has focused on chronic stress patterns in the brain,” says Chen. “In addition to presenting a possible new target for treating the diseases that arise from chronic stress, the findings of this study will open new directions for future research.”