A deeper look inside the sleeping bird brain

Similarities and differences between avian and mammalian sleep and possibly memory consolidation

Birds have good memories, but in contrast to mammals, little is known about how they consolidate memories during sleep. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology and Utrecht University recorded waves of slow activity traveling through the brain of sleeping pigeons that are very similar to those observed in mammals. However, they could not detect other brain rhythms known to be important for certain types of memory consolidation in mammals. They therefore suggest that birds may process some memories in a different manner from mammals.

Sleep in birds and mammals is very similar with two distinct sleep phases. During rapid eye movement (REM) sleep the eyes twitch, the muscles relax and the brain is active, but the animal is less responsive to its surroundings. The other sleep state is slow-wave sleep, also known as non-REM sleep. In mammals, this is the state where long-term memory formation is thought to happen, when a combination of three brain rhythms in the hippocampus and neocortex work together to gradually transfer short-term memory from the hippocampus to the neocortex for long-term storage.

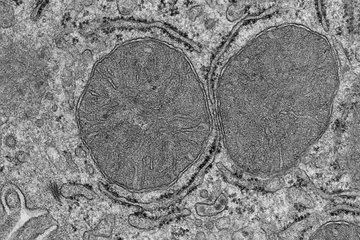

The three brain rhythms involved are neocortical slow-waves, thalamocortical spindles, and the so-called hippocampal sharp-wave ripples. “In birds, only slow-waves have been detected in electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings from the surface of the brain”, says Jacqueline van der Meij, first author of the study. “Given that birds are well known for their long-term memory, we wondered whether spindles were lurking undetected deeper in their brains.” The researchers measured brain activity across the layers of the hyperpallium – the avian version of the neocortex – in naturally sleeping pigeons.

Only slow-waves in the avian brain

As in the surface EEGs from various birds, only slow-waves were detected deeper in the brain during NREM sleep in pigeons. Interestingly, as in the mammalian neocortex, slow-waves appeared first in specific parts of the hyperpallium and spread out as travelling waves of activity. However, spindles were not detected. “The absence of spindles might be linked to differences between how mammals and birds store hippocampal memories” says Niels Rattenborg, who led the study. “In mammals, memories initially stored in the hippocampus transfer to the neocortex over time. However, as memories are not known to transfer out of the avian hippocampus, birds may have no need for spindles.” Nonetheless, Jacqueline van der Meij notes, “Our findings indicate that traveling slow-waves, a trait shared by mammals and birds, may be involved in more general processes unrelated to transferring hippocampal memories in both groups.”