The music in our speech

Daniela Sammler conducts research into the structures of the brain that process speech and music, and finds many commonalities

A mother sings a lullaby to her baby. When she talks to her child she modifies the pitch of her voice. What the baby “understands” is the melody and the emotions that this expresses.

Daniela Sammler, a neuropsychologist at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, considers both musical melodies and speech melodies to be the “social glue” or the “lowest common denominator in human evolution”.

“Both obey a grammar – naturally culture-specific – that we learn early on in life. Speech is clearly governed by the order of clauses in a sentence,” explains the 38-year-old, who has led her own Research Group in Leipzig since the summer of 2013. But how individual words and parts of a sentence are stressed can also fundamentally change the meaning of a sentence. Take the sentence “Mary has given a book to John”, where the meaning depends on whether Mary or John has been stressed.

Music, similarly, follows a sequence of tones and harmonies – its “musical grammar.” If a pianist, for example, breaks these rules, brain regions activate that are astonishingly similar to those that fire when grammatical mistakes are made in a sentence.

Music and speech: two channels of communications only available to humans

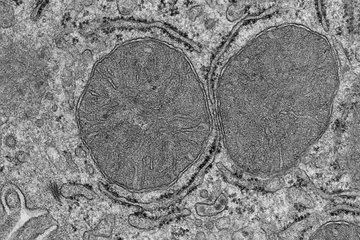

Daniela Sammler doesn't consider it chance that we humans alone, among all other animals, possess both speech and music as channels of communication. She is convinced that over the course of evolution the human brain has evolved to process both. And she has set out to uncover the underlying structures of the brain. One part of the Research Group she leads investigates the role of speech melodies – word stress, the sequence of pitches in a sentence, and the cadence of speech. The other part researches how melodies are perceived in music. To do this she has had a special piano constructed by the Julius Blüthner piano manufacturing company in Leipzig that can be played while in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner. With its help scientists can measure the brain activity of pianists while playing the piano. What's really fascinating is how our sense for the rules of music governs how we interpret it. Both of these investigations suggest that similar regions of the brain are employed to process melodies in both speech and music, and colleagues in the same scientific circles are taking note: “Thanks to the intensive research that Daniela Sammler has undertaken, we now know that the neuronal substrates of music and speech are more similar than we ever suspected,” says Angela Friederici, Director at the same Institute. “It’s her work that has demonstrated the central role of speech melody in our interpersonal communication.”

“Our brains don’t have separate specialized regions for speech and for music,” stresses Daniela Sammler. Music, like speech, activates a number of brain regions that are often also responsible for other functions. “Take hearing for example, and also motor function – like tapping your foot. Not to forget the emotional centres, like those used to store memories,” adds Sammler. In the brain, different highly interconnected regions all work together. In the process, similar tasks are bundled together in specialized regions. How this happens in detail is what Daniela is hoping to understand.

What unites and what separates individual cultures?

For this reason she is investigating both the “universals” – the commonalities that exist in our understanding of music and speech across many cultures – as well as the culturally-learned differences. Do speakers of Arabic who understand no German have the same experience of German sentence melodies that a native German speaker might have? Is the reverse also true? Do we recognize a critical tone in the cadence of speech whether or not we speak the language?

Daniela Sammler is fascinated by this and many other new projects, and her students are often astonished at how analogous the results of speech and music research are. She supervises four doctoral students in her Group, as well as an ever-changing number of undergraduates. What are her further plans? “What I’m interested in could go on forever,” says Sammler. She recently submitted her German Habilitation (extended postdoctoral qualification), and she is now in the process of applying for vacant posts as a professor. Her scientific journey is ongoing in other words. She hopes to stay in Germany, or at least in Europe.

Text: mez / ba