Cells inherit protection from sunburn

Stress granules protect cells from the effects of UV radiation

UV radiation in the sunlight causes sunburn and increases the risk of skin cancer by damaging our DNA but also our RNA. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Freiburg, Germany, have now unveiled a cellular shield that protect cells from the harmful effects of damaged RNA caused by ultraviolet radiation. When cells divide, they pass on a defense system to their daughter cells. This system involves special stress granules formed by the enzyme DHX9 that capture damaged RNA to keep the new cells healthy.

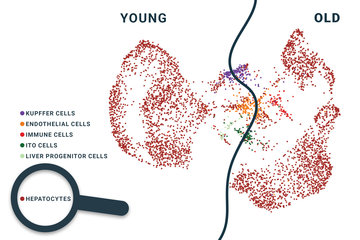

Mothers and daughters have a strong bond, yet do you know that connections reminiscent of this close relationship extend all the way to the cellular level? During the process of cell division, new daughter cells inherit a mix of genetic material and other molecules from their mother cells. This inheritance includes both beneficial components, which can help them for a robust start in life, and potentially harmful mutations or damaged molecules, posing significant challenges for the newly born daughter cells.

How daughter cells manage and mitigate the effects of harmful inheritance has remained a mystery. A study from the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics has now revealed a sophisticated mechanism by which daughter cells safeguard themselves against UV-damaged RNA inherited from mother cells.

As the sun's rays touch our skin, they bring warmth and vitality. Yet, beneath this gentle embrace lies a potential threat: ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the most energetic component of sunlight. Although we're familiar with how UV damages DNA and can lead to skin cancer, its impact on another vital molecule, RNA, often goes unnoticed.

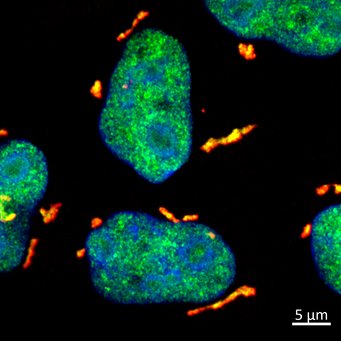

While testing the cellular response to various stressors, researchers noticed something intriguing: after UV radiation, a protein called DHX9 gathered into droplet structures within the cell's cytoplasm. “DHX9 is an enzyme that normally resides in the nucleus and has the ability to bind RNA. Finding this protein forming droplets outside the nucleus left us really astonished. It's like finding a giant snowball in the desert,” says Asifa Akhtar, Director at the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics.

Unravelling the mystery of DHX9 granules

Since UV radiation is widely known to cause DNA damage, the researchers initially suspected that these DHX9 granules act as a defence mechanism against such damage. “Contrary to this hypothesis, we found that DHX9 granules were not triggered by various forms of DNA damage stimuli. And this prompted us to dig into the real trigger,” says Yilong Zhou, the study's first author. Therefore, the team developed a groundbreaking droplet extraction method to isolate these granules directly from cells and analyze their content.

Surprisingly, the team found that the DHX9 granules, as a special type of stress granule, were packed with damaged RNA. “The damaging effect of UV light on RNA is frequently underestimated, overshadowed by its impact on DNA. Now, we discovered an elegant mechanism by which cells can segregate and neutralize harmful UV-damaged RNA with the help of DHX9 granules,” explains Asifa Akhtar. When cells detect RNA damage induced by UV exposure, they rapidly trap the damaged molecules into DHX9 granules, thereby preventing them from causing further harm. This safeguarding mechanism effectively confines the damage and ensures that it doesn't spread uncontrollably within the cell causing further chaos.

A safeguard mechanism in daughter cells

“What fascinated us even more was the observation that cells with DHX9 granules always appeared in pairs, indicating that they are not formed in the original UV-damaged mother cell but later on in the newly born daughter cells,” says Yilong Zhou. The hypothesis is confirmed by live cell video imaging. “You can literally see that DHX9 normally resides in the nucleus, but shortly after cell division, when the two daughter cells have formed, it gathers into droplets in the cytoplasm,” Zhou continues.

Interestingly, preventing DHX9 granule formation in daughter cells leads to severe cell death, highlighting the ability of daughter cells to spot and stash away their progenitors’ damaged RNA into DHX9 granules. “This process is like wiping the slate clean, preparing them to begin their own journey as a cell without dragging along the baggage from the previous generation,” says Asifa Akhtar.

Understanding how our daughter cells defend themselves against UV-induced parental RNA damage not only deepens our understanding of the cell cycle but also opens up new possibilities for medical research. Conditions such as sunburn, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer are intricately tied to disruptions in RNA balance and irregularities in the cell cycle. “A better understanding of how a newly generated cell selectively recognizes and degrades damaged RNA could lead to new therapeutic targets for diseases characterised by RNA mismanagement or dysregulation of the stress response,” explains Asifa Akhtar.

AA/YZ/MR