“We want to open up opportunities”

On the Africa strategy of the Max Planck Society

Africa is a continent with great research potential. The Max Planck Society has actively conducted research in Africa for a considerable period of time. Currently, we are exploring ways to provide enhanced support to African scientists on the ground. The inaugural "Africa Round Table" (ART) was held on December 15, 2020, initially conducted virtually due to the ongoing pandemic situation.

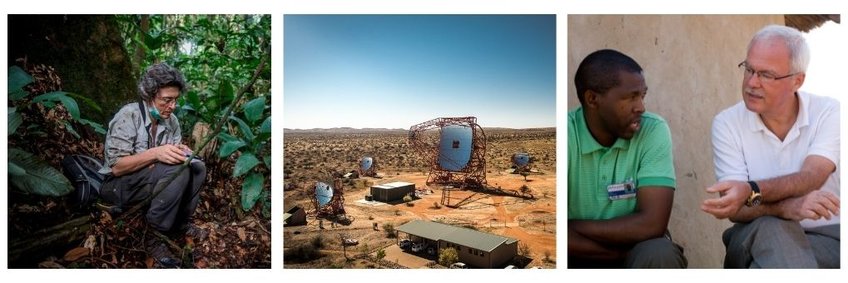

The MPI for Evolutionary Anthropology maintains field stations for behavioural research on great apes in the Congo and the Ivory Coast. Teams from the MPI for Animal Behaviour are on the move in Kruger National Park to record animal movements there with GPS transmitters. The MPI for Psycholinguistics is investigating linguistic diversity in different regions of Africa. And with H.E.S.S. in Namibia or the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in South Africa, huge measuring instruments for astronomy have been created with the cooperation of Max Planck Institutes.

"I myself have been carrying out research in Africa since 1991," says Bill Hansson, the newly appointed chair of the "Africa Round Table." "For all of us, Africa is truly a remarkable place for research. However, I have often sensed that our contributions do not match what we receive. It's time to bridge the gap and ensure African researchers have an equal and prominent place in the scientific landscape."

Africa’s population is young – half of its billion-plus inhabitants are under 19. And even if the young Africa of smartphones and solar cells has not yet quite conquered established politics, it continues to shape and develop societies. “Education is a catalyst for unlocking this potential, but it must be approached with sensitivity and respect. Avoiding post-colonial dynamics means empowering African scientists to make their own choices regarding the opportunities presented to them.” says Hansson.

As a first step towards fostering collaboration, the Max Planck Society aims to implement accessible initiatives such as lectures and mentorship programmes. There will also be a special partner group programme and mobility grants for African scientists interested in temporary work at a Max Planck Institute in Germany. “Ensuring that returning junior scientists have a strong foundation upon their return home is also a crucial aspect,” Hansson explains. However, the larger challenge lies in creating a sustainable scientific environment with suitable research conditions. How do you make a science system work? “Solely looking at European institutions like Max Planck or the French CNRS is not the way forward in establishing an effective science system.” Hansson explains

We must ensure that research policies and funding mechanisms in Africa are designed to be effective within the local context," emphasizes Hansson, drawing upon his extensive experience. Since 2006, he has served on the board of the International Centre for Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) in Kenya. “When I joined the board, the institute was close to bankrupt – we more or less had to borrow money to pay the salaries,” Hansson says. But with strong local management in combination with an active Governing Council, the Center is now on a very good path. “Today, icipe serves as a model institute in Africa.”

International donors seek trustworthy and efficient organizations to channel their funds effectively. “icipe exemplifies such an organization. It has a multi-million dollar budget primarily sourced from “soft” money such as endowment funds”, Hansson points out. He aims to collaborate closely with the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, leveraging its extensive alumni network in Africa, to explore additional funding avenues. One thing is already clear: the Max Planck Society must demonstrate long-term commitment and vision for Africa - there are no instant solutions or quick fixes.

Text: Christina Beck