Measuring the brain

Scientists discover two spatially separate sub-areas within the anterior cingulate cortex of mice

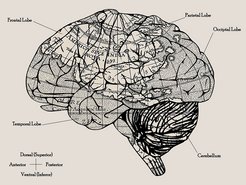

Maps of the brain are an important tool to understand how the brain works. Unless the map is wrong. In a recent study ESI group leader Martha Nari Havenith and colleagues show that a lot of the research looking at emotional and cognitive processing in rodents relies on a mapping system that doesn’t make sense.

When Christopher Columbus made landfall in San Salvador in 1942, he was convinced he had reached Asian shores. If he, like Amerigo Vespucci some years later, had attempted to draw a map of the coastal line, he would have noticed his mistake. “Maps are powerful tools that can help us to make sense of the world while we draw them,” says Martha Nari Havenith, who is one of ESI’s group leaders. In a recent publication she and her team demonstrate that many researchers working with mice stick to a brain map that – figuratively speaking – makes them believe they are in Asia, while truly they stepped ground in the Americas.

Just like geographers have created maps detailing every corner of the earth, neuroscientists are creating maps that chart different properties of the brain. This way they are trying to work out the boundaries between brain areas that fulfill different tasks. However, compared to how much we know about earth, we are only just starting to understand the brain, which is why modern day neuroscientists every now and then may be facing problems similar to those the explorers of the new world had: Their maps sometimes reflect what is commonly accepted to be, rather than what really is. Martha Nari Havenith and colleagues found this to be particularly true for certain areas of mouse and rat brains.

Different findings

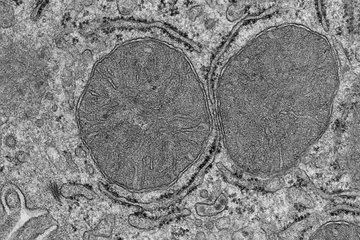

“I would never have noticed, if my PhD student Sabrina hadn’t been so diligent in comparing her findings to the literature,” remembers Martha Nari Havenith. Sabrina van Heukelum had investigated the function of a brain area called anterior cingulate cortex, or short ACC. ACC plays an important role in making sure we behave appropriately to a situation at hand, by processing emotional information and keeping impulsive behavior in check. In experiments with mice, Sabrina van Heukelum was digging into the mechanism through which ACC controls aggressive behavior. What she observed was that based on anatomical characteristics ACC could be divided in two spatially separate sub-areas: Comparing aggressive mice with less aggressive mice, one of the two areas was increased in volume, while the other was decreased.

A clear-cut finding and one that fits what is known from humans and monkeys. There, based on detailed mapping of neuronal function, a big part of ACC has been defined as a separate area, called midcingulate cortex, or MCC. While ACC is an expert for processing emotions, MCC has a stronger affinity for solving cognitive tasks.

For mice however a similar division of labor in cingulate cortex is not well established, explains Martha Nari Havenith: “Initially we thought the research looking at cingulate cortex in mice is still in its infancy and that would explain why the effect we found isn’t as clear for rodents.” But then Sabrina van Heukelum started to dig deeper. She compared her own data with what was reported in the literature and realized: Many studies would probably have been able to describe the same effect she had found, if they had used the same brain map.

Different maps

The maps that are most commonly used in order to navigate through brains of rats and mice do not partition cingulate cortex on the grounds of a functional division into ACC and MCC as it is common for most species (including humans). They use a historic partitioning that divides cingulate cortex in two areas called Cg1 and Cg2 that are located perpendicular to where the ACC/MCC border would be. “When we used the Cg1/Cg2 convention for our own data, the result just looked like noise,” explains Sabrina van Heukelum. The influence of cingulate cortex in controlling aggressive behavior did not get apparent because the differences in volume were thrown together and zeroed each other out.

Other researchers have previously pointed out that it would make more sense to agree on a functionally defined cross-species definition of brain areas and drop historic definitions for individual species. The work by Martha Nari Havenith and her group is the first to illustrate how dramatically this may impact scientific insight. “When it comes down to it, neuroscientists are not researching rodents to better understand mice. We want to understand the brain across species,” concludes the ESI researcher.

The scientists hope their finding will bring other researchers to stop using the established but outdated rodent charting system so they have better chances to realize when they are in neuronal Asia and when they discovered America.