Human ancestors may have regularly climbed trees

A hominin species regularly adopted highly flexed hip joints, a posture associated with climbing trees

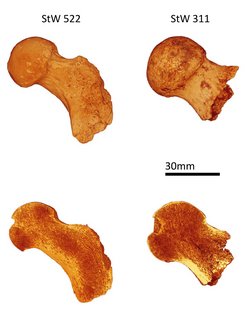

These findings came from analysing and comparing the internal bone structures of two fossil leg bones from South Africa, discovered over 60 years ago and believed to have lived between one and three million years ago. For both fossils, the external shape of the bones were very similar showing a more human-like than ape-like hip joint, suggesting they were both walking on two legs. The researchers examined the internal bone structure because it remodels during life based on how individuals use their limbs. Unexpectedly, when the team analysed the inside of the spherical head of the femur, it showed that they were loading their hip joints in different ways.

The research project was led by Leoni Georgiou, Matthew Skinner and Tracy Kivell at the University of Kent’s School of Anthropology and Conservation, and included a large international team of biomechanical engineers and palaeontologists, including Jean-Jacques Hublin, director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. These results demonstrate that novel information about human evolution can be hidden within fossil bones that can alter our understanding of when, where and how we became the humans we are today.

"It is very exciting to be able to reconstruct the actual behaviour of these individuals who lived millions of years ago and every time we CT scan a new fossil it is a chance to learn something new about our evolutionary history," said Leoni Georgiou. Matthew Skinner said: "It has been challenging to resolve debates regarding the degree to which climbing remained an important behaviour in our past. Evidence has been sparse, controversial and not widely accepted, and as we have shown in this study the external shape of bones can be misleading. Further analysis of the internal structure of other bones of the skeleton may reveal exciting findings about the evolution of other key human behaviours such as stone tool making and tool use. Our research team is now expanding our work to look at hands, feet, knees, shoulders and the spine."

University of Kent/SJ