The brains of jazz and classical pianists work differently

The brain activity of jazz pianists differs from those of classical pianists, even when playing the same piece of music.

A musician’s brain is different to that of a non-musician. Making music requires a complex interplay of various abilities which are also reflected in more strongly developed brain structures. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) in Leipzig have recently discovered that these capabilities are embedded in a much more finely-tuned way than previously assumed—and even differ depending on the style of the music: They observed that the brain activity of jazz pianists differs from those of classical pianists, even when playing the same piece of music. This could give insight into the processes which generally take place while making music and which are specific for certain styles.

Keith Jarret, world-famous jazz pianist, once answered in an interview when asked if he would ever be interested in doing a concert where he would play both jazz and classical music: “No, that's hilarious. […] It’s like a chosen practically impossible thing […] It's [because of] the circuitry. Your system demands different circuitry for either of those two things.“ Where non-specialists tend to think that it should not be too challenging for a professional musician to switch between styles of music, such as jazz and classical, it is actually not as easy as one would assume, even for people with decades of experience.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) in Leipzig demonstrated that there could be a neuroscientific explanation for this phenomenon: They observed that while playing the piano, different processes occur in jazz and classical pianists’ brains, even when performing the same piece.

Different priorities

“The reason could be due to the different demands these two styles pose on the musicians—be it to skilfully interpret a classical piece or to creatively improvise in jazz. Thereby, different procedures may have established in their brains while playing the piano which makes switching between the styles more difficult”, says Daniela Sammler, neuroscientist at the MPI for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences and leader of the current study about the different brain activities in jazz and classical pianists.

One crucial distinction between the two groups of musicians is the way in which they plan movements while playing the piano. Regardless of the style, pianists, in principle, first have to know what they are going to play—meaning the keys they have to press—and, subsequently, how to play—meaning the fingers they should use. It is the weighting of both planning steps, which is influenced by the genre of the music.

According to this, classical pianists focus their playing on the second step, the 'How'. For them it is about playing pieces perfectly regarding their technique and adding personal expression. Therefore, the choice of fingering is crucial. Jazz pianists, on the other hand, concentrate on the 'What'. They are always prepared to improvise and adapt their playing to create unexpected harmonies.

“Indeed, in the jazz pianists we found neural evidence for this flexibility in planning harmonies when playing the piano”, states Roberta Bianco, first author of the study. “When we asked them to play a harmonically unexpected chord within a standard chord progression, their brains started to replan the actions faster than classical pianists. Accordingly, they were better able to react and continue their performance.“ Interestingly, the classical pianists performed better than the others when it came to following unusual fingering. In these cases their brains showed stronger awareness of the fingering, and consequently they made fewer errors while imitating the chord sequence.

Imitating cord sequences in silence, using a muted piano

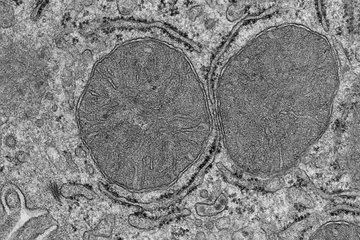

The scientists investigated these relations in 30 professional pianists; half of them were specialized in jazz for at least two years, the other half were classically trained. All pianists got to see a hand on a screen which played a sequence of chords on a piano scattered with mistakes in harmonies and fingering. The professional pianists had to imitate this hand and react accordingly to the irregularities while their brain signals were registered with EEG (Electroencephalography) sensors on the head. To ensure that there were no other disturbing signals, for instance acoustic sound, the whole experiment was carried out in silence using a muted piano.

“Through this study, we unravelled how precisely the brain adapts to the demands of our surrounding environment”, says Sammler. It also makes clear that it is not sufficient to just focus on one genre of music if we want to fully understand what happens in the brain when we perform music—as it was done so far by just investigating Western classical music. “To obtain a bigger picture, we have to search for the smallest common denominator of several genres”, Sammler explains. “Similar to research in language: To recognise the universal mechanisms of processing language we also cannot limit our research to German”.