How the brain decides what we perceive

Patterns of brainwaves in the prefrontal cortex gate access to consciousness

Perception is highly selective; the brain constantly decides what information is important enough to reach our consciousness. An international team of researchers has now shed light on brain activities associated with subjective perceptual shifts, finding characteristic patterns of brain waves in the prefrontal cortex. Their findings could contribute to refining our understanding of consciousness.

What we see is not what we perceive: a large part of the sensory information that constantly arrives through our senses is never consciously processed. Complex mechanisms in the brain filter the incoming sensory information and shape the representation of the world in our minds. The phenomenon of binocular rivalry provides a prime example for this: when a rose is presented to the left eye and an apple to the right eye (which can be achieved via a setup of mirrors), we cannot perceive both objects at the same time. Rather, sometimes we see the rose, while at other times we become conscious of the apple. This perceptual switch happens spontaneously, unprompted by external stimuli. This raises the question of what intrinsic mechanism in the brain underlie them.

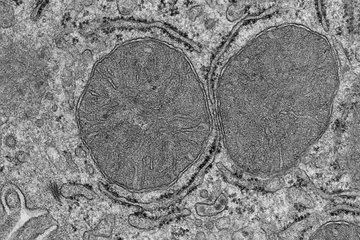

Researchers have now uncovered some of the inner workings of conscious perceptions. Interestingly, the perceptual switches can be predicted from the pattern of brain waves in the prefrontal cortex, a brain area implicated in complex behavior such as decision-making and problem-solving. Brain waves are a normal activity of the healthy brain; they result from synchronized activities of larger ensembles of neurons. Beta waves, for example, are oscillations typically associated with active thinking and concentration, while certain slower waves are linked to sleep or rest.“We found typical patterns in low-frequency (1 to 9 Hertz) and beta waves (20 to 40 Hertz) just before the perceptual switches occurred”, says Abhilash Dwarakanath, previously a member of Nikos Logothetis’ Department for Physiology of Cognitive Processes at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen and now a researcher at NeuroSpin, Paris. Together with Vishal Kapoor, likewise a former member of Logothetis’ team and now a principal investigator at the International Center for Primate Brain Research in Shanghai, Dwarakanath led the efforts to interpret the data obtained from electrophysical recordings of macaque monkeys.

Their results challenge a previously dominant belief. In the primary visual cortex, the brain area where visual input arrives first, some neurons are solely in charge of relaying information from only one eye. Neuroscientists used to believe that the rivalry of these neurons vying for attention of the higher brain areas caused the switches in perception. “For a long time, people thought that the spiking of single neurons was the main currency of conscious perceptions”, says Dwarakanath. “But it turns out that it is actually the much slower oscillations of larger brain areas that do the dirty work; they are the gatekeepers who decide which sensory input gets to access our consciousness.”

Refining a theory of consciousness

Dwarakanath stresses that it is impossible to decipher any sort of content from the brain wave patterns: “All we can say is that whenever we observe the specific pattern, a switch in perception will occur; we cannot decode the content of consciousness from the waves.” He also cautions that it is impossible to deduce from the data if the brain wave patterns cause the switch, or if they merely precede it.

The findings touch upon deeper questions – debated by philosophers and neuroscientists alike – of how conscious experience can emerge from the brain. Theofanis Panagiotaropoulos, the senior researcher who initially conceived and supervised the project, calls their new results a “refinement of the global workspace theory”, a theory of consciousness which attributes a central role to the prefrontal cortex. Panagiotaropoulos is involved in a large collaboration that aims to test the two main competing theories of consciousness; he is confident that the observations about perceptual switches will bring neuroscience a step closer to an accurate theory of consciousness.