Nobel Prizes

Since 1901, the Nobel Prize has been awarded in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature and peace efforts. Internationally, the Nobel Prize is considered to be the highest distinction in the various disciplines. The prize, which was instituted by Swedish inventor and industrialist Alfred Nobel, is to be distributed to “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind”, according to his will. Since 2001, the prize amount, which is derived from the income in interests on the Foundation’s investments, is set to 10 million Swedish kronor per category. To date, the following scientists from the Max Planck Society and its predecessor the Kaiser Wilhelm Society have been awarded the Nobel Prize.

In retrospect, the research awarded in this way reflects an important piece of scientific history since the beginning of the 20th century. The relevance of many of the works is particularly evident in the long term. The Max Planck Society counts 31 award winners in the natural science disciplines. In the year the prize was awarded, they were scientific members of the Max Planck Society or of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society as its predecessor.

Other scientists were no longer or not yet Scientific Members at the time the prize was awarded, but had carried out the most important part of their research in the Max Planck Society or had left a lasting mark on it through their commitment to research and administration.

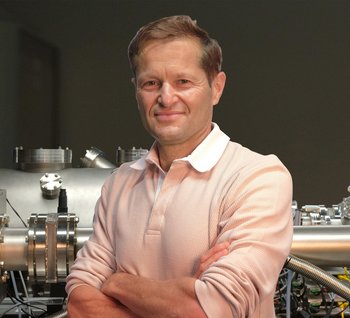

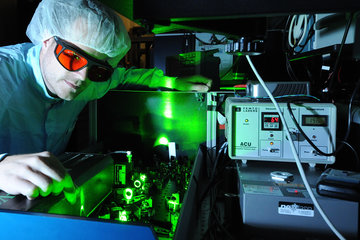

2023 - Nobel Prize in Physics

Ferenc Krausz, Director at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics and Professor at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, together with Pierre Agostini and Anne L'Huillier, has been honoured with the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physics. The Nobel Committee is honouring the two reserachers for the foundation of attosecond physics. An attosecond is the billionth part of a billionth of a second. Laser pulses lasting only a few attoseconds can be used to track the movements of individual electrons. This not only provides fundamental insights into the behaviour of electrons in atoms, molecules and solids, but could also help to develop electronic components more quickly.

2022 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Medicine 2022 was awarded to Svante Pääbo "for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution". Pääbo succeeded in making the genetic material of extinct early humans available with more efficient extraction and sequencing methods. In 2010, he and his team were able to reconstruct a first version of the Neanderthal genome from bones that are tens of thousands of years old. He thus laid the foundation for the new discipline of palaeogenetics, which has revolutionised our understanding of the evolutionary history of modern humans within just a few years.

More information in the Digital Story

2021 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2021 was awarded jointly to Benjamin List and David W.C. MacMillan "for the development of asymmetric organocatalysis." The two researchers had discovered that small organic molecules also mediate chemical reactions. Previously, it was assumed that only enzymes and metals, including often toxic heavy metals or expensive and rare precious metals, could accelerate chemical reactions and steer them in a desired direction. It is particularly interesting that the small organic molecules are suitable for so-called asymmetric synthesis: In this process, only one of two enantiomers is formed - these are molecules that are like the left and right hand, i.e. cannot be spatially aligned. Such molecules are involved in all biological processes and also play an important role as medical agents.

More information in the Digital Story

2021 - Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2021 was awarded "for pioneering contributions to the understanding of complex systems". One half goes jointly to Klaus Hasselmann and Syukuro Manabe "for the physical modelling of the Earth's climate, the quantification of fluctuations and the reliable prediction of global warming" and the other half to Giorgio Parisi "for the discovery of the interplay of disorder and fluctuations in physical systems from atomic to planetary scales".

More information in the Digital Story

2020 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2020 was awarded jointly to Emmanuelle Charpentier from the Max Planck Research Unit for the Science of Pathogens (at the time of the awarded research at the University of Vienna and Umeå University) and Jennifer A. Doudna "for the development of a method for genome editing." The two award winners have described how the CRISPR-Cas9 system targets DNA and how it can be used as a versatile genetic tool to alter the genome. They have contributed significantly to the development of the CRISPR-Cas9 technology into a powerful and versatile tool that can be used to efficiently alter any gene sequence in the cells of living organisms.

More information in the Digital Story

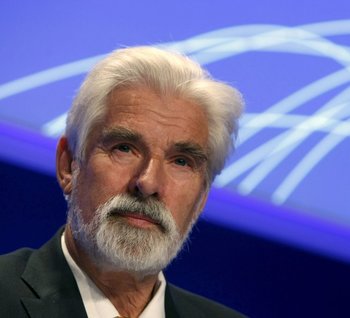

2020 - Nobel Prize in Physics

Reinhard Genzel, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, received the Nobel Prize for Physics 2020 together with Roger Penrose and Andrea Ghez. The Royal Swedish Academy honours the scientists for their black hole research. Using high-precision methods, the group around Genzel also observed bursts of brightness from gas in the immediate vicinity of the black hole and a gravitational redshift caused by this mass monster in the light of a passing star.

More information in the Digital Story

2014 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In 2014, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry went to three researchers: Stefan W. Hell (Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen), Eric Betzig (Howard Hughes Medical Institute) and William E. Moerner (Standford University) in honour for their contributions to nano-optics, with which they have overcome the physical resolution limit of optical microscopy and imaging with a chemical trick.

More information in the Digital Story

2007 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In 2007, Gerhard Ertl was honoured for his work on chemical processes on solid surfaces. His studies formed the basis for our understanding of industrial catalysts and catalytic processes. This means that today we are able to understand very different processes, such as the function of fuel cells or of catalysts in cars. Chemical reactions on catalytic surfaces play a vital role in many industrial operations, such as the production of artificial fertilizers.

More information in the Digital Story

2005 - Nobel Prize in Physics

In 2005, Theodor W. Hänsch and the Americans Roy J. Glauber and John L. Hall were honoured for their research on spectroscopy. Hänsch and Hall received the coveted prize “for their contributions to the development of laser-based precision spectroscopy, including the optical frequency comb technique”. The scientists developed an optical frequency comb generator, which made it possible, for the first time, to count the number of light oscillations per second accurately. Such optical frequency measurements may be million-fold more accurate than determining the light wavelengths using conventional spectroscopy.

More information in the Digital Story

1995 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

Biologist Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard received the distinction together with Edward B. Lewis and Eric F. Wieschaus for their research on the genetic control of early embryonic development. Using the egg of the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), Nüsslein-Volhard and Eric Wieschaus identified and classified genes that determine the body plan and the formation of body segments. They developed the gradient theory, which describes how gradients in the egg and in the embryo control the gene expression, drawing parallels in embryonic development between insects and vertebrates.

More information in the Digital Story

1995 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The work of Paul Crutzen, Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland in atmospheric chemistry has largely contributed to explaining the chemical processes that cause ozone to form and decompose. They demonstrated, among other things, how sensitive the ozone layer is to the anthropogenic emission of air pollutants.

More information in the Digital Story

1991 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

More information (Erwin Neher) in the Digital Story

More information (Bert Sakmann) in the Digital Story

1988 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

More information (Robert Huber) in the Digital Story

More information (Hartmut Michel) in the Digital Story

More information (Johann Deisenhofer) in the Digital Story

1986 - Nobel Prize in Physics

One half of the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Ernst Ruska for his “fundamental work in electron optics and for the design of the first electron microscope” (the other half was awarded jointly to Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer, IBM Research Laboratory, Zurich, Switzerland, for their design of the scanning tunnelling microscope). Ernst Ruska’s invention is one of the most important of this century. Its development began with work carried out by Ruska as a young student at the Berlin Technical University at the end of the 1920s. He found that a magnetic coil could act as a lens that could be used to obtain an image of an object irradiated with electrons. By coupling two such electron lenses, he produced a primitive microscope. Ruska very quickly improved various details and in 1933 was able to construct the first electron microscope with a performance clearly superior to that of conventional light microscopes. The scientist subsequently contributed actively to the development of commercial mass-produced electron microscopes which rapidly found application within many areas of science.

More information in the Digital Story

1985 - Nobel Prize in Physics

Klaus von Klitzing was awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the “quantised Hall effect”. He discovered that the unit for electric resistance (ohm) is accurately determined by Planck’s energy quantum h and the charge of the electrons e, and therefore constitutes a universal natural constant. The von Klitzing constant is a universal standard and highly accurate means of measuring resistance.

More information in the Digital Story

1973 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

Konrad Lorenz, Karl von Frisch and Nikolaas Tinbergen were awarded the Nobel Prize jointly “for their discoveries concerning the organisation and elicitation of individual and social behaviour patterns”. Lorenz combined his observations of animals in a concise physiological theory of instinctive activities, thereby paving the way for comparing the behaviour of different species. More consistently than scientists before him, Lorenz focused on two genetic particularities in his work: innate triggers of behaviour patterns (“key stimuli” and “innate releasing mechanisms”) and an early critical period of development in various animal species, in which an “imprinting process” elicits an irreversible behaviour pattern.

More information in the Digital Story

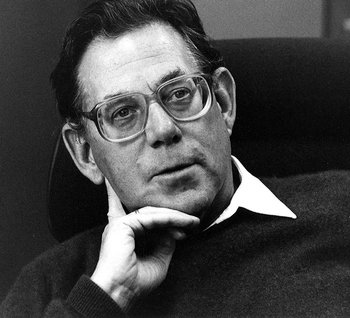

1967 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Manfred Eigen shared the Nobel Prize with Ronald George Wreyford Norrish and George Porter “for their studies of extremely fast chemical reactions, effected by disturbing the equilibrium by means of very short pulses of energy”. Eigen developed the relaxation methods for the study of faster reactions in the range of nanoseconds. The common characteristic of this method is that a chemical system in equilibrium is disturbed by singular (pressure, temperature, electromagnetic field) or periodic (sound waves) fast influences. This will cause small changes in concentration which vanish (comparatively slowly, given their smallness) as the equilibrium is re-established. Eigen developed these relaxation measurements to unsurpassed mastery and thus solved important questions in biochemistry, such as that of the control of enzymatic activities, which in turn regulate many metabolic processes in the cell.

More information in the Digital Story

1964 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

Konrad Bloch and Feodor Lynen received the Nobel Prize jointly “for their discoveries concerning the mechanism and regulation of the cholesterol and fatty acid metabolism”. By succeeding in isolating activated acetic acid (acetyl coenzyme A) in yeast, Lynen established the basis for clinical research on lipid metabolism disorders, for example in Diabetes mellitus, or in the onset of atherosclerosis.

More information in the Digital Story

1963 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded jointly to Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta “for their discoveries in the field of the chemistry and technology of high polymers”. The discovery of organometallic compound catalysts made of aluminium and titanium, the Ziegler-Natta catalysts, transformed both chemistry as a science and the chemical industry and its technology. Using the catalysts, ethylene could, for the first time, be polymerised into polyethylene at atmospheric pressure. Until then, this had only been possible under extreme conditions (a pressure of 1000 at and temperatures of 200 degrees Celsius). Today, a global annual production of several billion tonnes makes polyethylene one of the most commonly used plastics. Due to its sought-after properties, it is very versatile.

More information in the Digital Story

1954 - Nobel Prize in Physics

Walther Bothe received the Nobel Prize for the coincidence method and his discoveries made therewith. He shared the prize with Max Born. The coincidence measurements proved the penetration of extraterrestrial radiation – cosmic radiation. When studying cosmic radiation, Bothe used Geiger-Müller tubes that were set up so that they only displayed a discharge if a particle passed through them linearly; this meant that it could be established from which direction the charged particles were coming. Indeed, the particles generally fell vertically towards the earth’s surface, however their incidence intensity would shrink to zero if the device was instead pointed towards the horizon. This seems logical, since particles which do not fall vertically would have to penetrate a much thicker air layer. The thicker the air layer, the fewer the particles that penetrate it – only those particles particularly rich in energy “make it through”.

More information in the Digital Story

1944 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Otto Hahn received the prize “for his discovery of the fission of heavy atomic nuclei”. It was the unplanned result of a joint research project with physicist Lise Meitner to investigate radioactive decay phenomena and the possible generation of transuranics by bombarding uranium atomic nuclei with neutrons. Meitner had fled Nazi Germany a few months before the discovery in 1938. But from exile, she provided the physical explanation of the chemical measurement results of Otto Hahn and Fritz Straßmann. Otto Hahn was one of the pioneers of radiochemistry research, which began around 1900. After the Second World War and in the wake of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he and other Nobel Prize winners appealed to politicians to use nuclear power only for peaceful purposes. He was President of the Max Planck Society from 1948 to 1960.

More information in the Digital Story

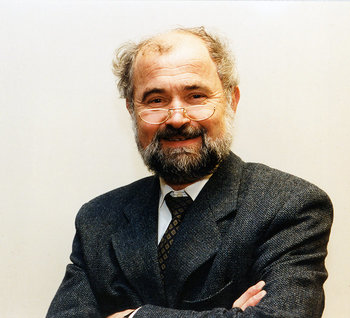

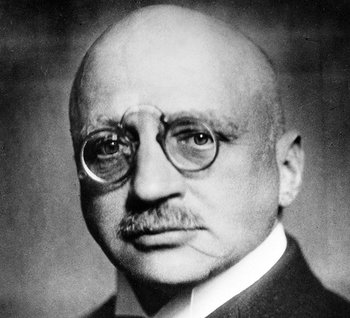

1939 -Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Adolf Butenandt shares the 1939 prize “for his work on sex hormones” with Leopold Ružička. Because Adolf Hitler had forbidden Germans to accept the Nobel Prize, Butenandt did not accept the award (without prize money) until 1949. Butenandt had been working on steroid hormones since the 1920s. He isolated the sex hormones oestrone, progesterone, and androsterone and elucidated their chemical structures. His research paved the way to hormone treatments and the development of the birth control pill. After the Second World War, Adolf Butenandt left a lasting mark on the West German scientific system. He was also President of the Max Planck Society from 1960 to 1972.

More information in the Digital Story

1938 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

For 1938, the prize went to biochemist Richard Kuhn for his work on carotenoids and vitamins. Like Adolf Butenandt, Kuhn did not accept the prize until 1949 because Adolf Hitler had forbidden Germans from doing so. Since the early 1930s, Kuhn had devoted himself to natural product chemistry and was able to elucidate and synthesize the structures of vitamins A and B12. Kuhn’s behaviour during National Socialism is viewed very critically today because from 1941, he participated in poison gas research and denounced his Jewish colleagues.

More information in the Digital Story

1936 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Physicist Peter Debye received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for “his investigations on dipole moments as well as on the diffraction of X-rays and electrons in gases”. He was one of the pioneers of quantum mechanics and the application of this to problems in solid-state physics. Among other things, he developed the theory of substance-specific heat on crystals and investigated the thermal conductivity of crystals. To this end, he also conducted experiments near absolute zero and operated one of the first refrigeration laboratories at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin of which he was also the Director. In 1940, Debye vacated his post because he did not want to take German citizenship (this was a condition of the Nazi regime to be allowed to continue in office as a Dutch native). He emigrated to the US, where he continued his career at Cornell University.

More information in the Digital Story

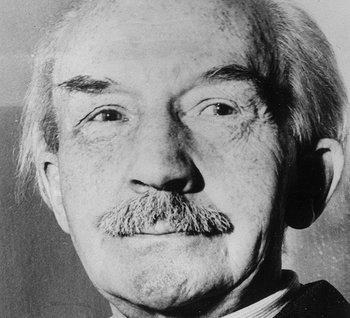

1931 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

The Nobel Commission awarded Otto Heinrich Warburg the prize “for the discovery of the nature and function of the respiratory enzyme”. They thus honoured his fundamental research on metabolic processes in plant and animal cells. In his banquet speech at the award ceremony, Warburg himself summed up the essence of his work: “Traces of a heavy metal compound transfer oxygen in living cells and thus free up the forces for what happens in the organic world”. Warburg was also interested in metabolic processes in cancer cells and developed novel standard measuring instruments for the biochemical laboratory. Although a member of a Jewish family, he was able to continue working at his Institute for cell physiology during the Nazi regime. It became the Max Planck Institute in 1953 and was closed after his death.

More information in the Digital Story

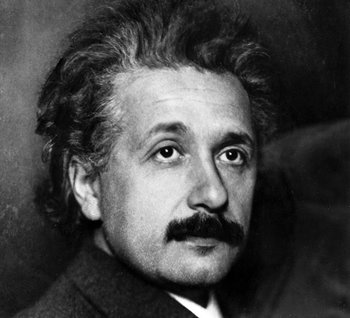

1921 - Nobel Prize in Physics

Albert Einstein received the prize “for his services to theoretical physics, especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect”, which he described in 1905. Contrary to the prevailing theory of James Maxwell – but in agreement with the radiation formula of Max Planck – Einstein assumed that light consisted of particles (photons) that could change the energy of electrons upon impact. This was an important step on the way to quantum mechanics.

However, Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity, which he published in 1915 as Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics in Berlin and which made him the most famous physicist of the 20th century, was not considered for the Nobel Prize. After the National Socialists came to power, Einstein, who had already been subjected to anti-Semitic attacks for years, did not return from a trip to the US. He applied for expatriation – without notable professional colleagues showing solidarity with him. In 1949, Einstein declined an invitation to become an External Scientific Member of the Max Planck Society citing the atrocities of National Socialism and the lack of sense of guilt in Germany.

More information in the Digital Story

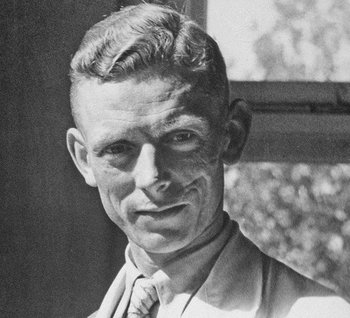

1918 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

“For the synthesis of ammonia from its elements” as they occur in the ambient air, Fritz Haber received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry at the end of the First World War. The committee paid tribute to him as a researcher who had solved the problem of the world food supply. Thanks to Haber’s process, which was brought to industrial maturity together with Carl Bosch, ammonia was now available in inexhaustible quantities. It provided the basis for the production of artificial fertilisers, the use of which revolutionized agriculture and made it many times more productive. However, Haber was also placed on the war crimes list of the victorious Allied powers in 1918 because he had developed poison gas weapons for the German troops in violation of the Hague Convention and had promoted the gas war side by side with the military. In 1933 Haber, who came from a Jewish family, resigned as Director of the Institute in protest against the new Nazi laws on the dismissal of Jews and fled to Switzerland in order to escape the National Socialists.

More information in the Digital Story

1915 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Richard Willstätter was awarded the Nobel Prize “for his studies of pigments, especially chlorophyll, in the plant kingdom”. His work provided fundamental insights into the composition of leaf and flower pigments. He identified magnesium as the central component of chlorophyll and the most important for photosynthesis. He did further work in anaesthesia, analgesics, and enzyme research. During the First World War, he developed a gas mask filter. Willstätter received a call to the University of Munich in September 1915, which he accepted in 1916. In 1924, he resigned from his professorship in protest against anti-Semitic movements at the university and emigrated to Switzerland during the Nazi regime.

More information in the Digital Story