Brain stimulation shows beneficial effects for motor deficits following stroke

This promising non-invasive method can be used for rehabilitation, provided that an individualised approach is developed

Persistent paralysis and coordination problems are among the most common consequences of a stroke. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, the University Medical Center Halle, and the Charité -Universitätsmedizin in Berlin have discovered that brain stimulation helps. Direct current, applied via electrodes attached to the head, led to significant improvement of patients’ impaired movements. In addition to showing pronounced effects after a single application, the study suggests that the therapy may need to be individually tailored to specific patients for optimal benefit.

Arm paralysis is one of the most common consequences of brain damage, for example, after a stroke. Those affected are often unable to use their arm at all or only to a very limited extent. The deficits are based on pronounced changes in both the physiology and structure of the brain. These changes result firstly from the direct damage caused by the stroke itself, but also extend to other regions due to how the brain is organized. "The basis of these changes are both reparative brain processes and behavioural patterns of everyday activities after the stroke. With the help of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), one can influence these changes in the brain. The currents penetrate the brain tissue, where they have a local excitatory or inhibitory effect," explains Bernhard Sehm, research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig and senior physician at the University Clinic and Polyclinic for Neurology at the University Medical Centre Halle. He and Toni Muffel of the Charité in Berlin investigated how this method impacts the rehabilitation of stroke patients and recently published their results in the journal "Brain Stimulation".

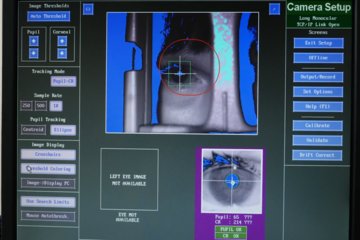

"Our study involved 24 patients who were very limited in their mobility due to the stroke. In the lab we have a robotic system that can be individually adapted to each patient, a kind of exoskeleton that enables them to move their paralysed arm and perform tasks in a virtual environment," explains Muffel, first author of the study. While the patients interacted with the virtual objects, their brains were stimulated via electrodes on the scalp. "In parallel, we measured how well, or how poorly, the brain stimulation helped the participants to perform the tasks."

The results? Brain stimulation had a clear impact on the brain areas affected by the stroke. "Our robotic system allows us to measure various motor functions simultaneously and thus gain a comprehensive picture of the stimulation effects. The data show that sensorimotor functions of the paralysed arm are clearly influenced by tDCS," explains Bernhard Sehm. "However, we could not identify a uniform beneficial pattern across different patients. Instead, the changes in the brain areas varied depending on the task and the electrode placement. This means that in the future, patients will need to be closely examined before brain stimulation treatment in order to develop a targeted and individualised approach to their deficits. This simple but promising method of brain stimulation will then have a future in patient care," concludes Bernhard Sehm.