“One has to be on the ground in Africa for that”

Looking back at one of the first Max Planck Research Groups in Africa

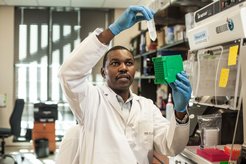

In 2012, the Max Planck Society broke new ground and set up research groups in Africa for the first time. The reason for this was that two of the most dangerous infections, HIV and tuberculosis (TB), entered into a fatal liaison in South Africa and other African countries: Due to the weakening of their immune system, HIV patients are particularly vulnerable to the tuberculosis pathogens. In this interview, former Max Planck Research Group leader Thumbi Ndung'u talks about his science, building research capacity in Africa, its impact on public health, and why none of this would have been possible from a Max Planck Institute in Germany.

Professor Thumbi Ndung'u, you led one of the research groups in Africa established by the Max Planck Society in 2012 and conducted basic research on HIV and tuberculosis. What have you achieved during the last few years?

Thumbi Ndung'u: Thanks to the guaranteed funding of the Max Planck Society during the last nine years, we were able to make significant progress in understanding the nature of the HI viruses that are being transmitted in the current HIV epidemic. Today, we know more about how those viruses and how the immune system responds immediately following HIV infection. This is necessary both for prevention and treatment of HIV, particularly HIV cure interventions. Our work has advanced the understanding of how to prevent or cure HIV by harnessing the immune system. Furthermore, I have been involved in HIV-Tuberculosis coinfection studies, looking at how HIV affects immune responses to tuberculosis (TB). That area of my research has also benefited strongly from the support of Max Planck.

Although you were a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology in Berlin, you worked in Durban in South Africa in close proximity to the major infection centres. Why?

Most of my work is based on learning from patients. In South Africa, thousands of people are infected both with HIV and TB. In order to get access to blood and tissue samples from these patients, I need to be where they are. As my work involves building cohorts of patients that can be followed over time, it has to be done in South Africa. It's much easier to work within the population that is affected, recruit patients, follow them up, build some rapport with those patients and try to help them by translating that knowledge in the local situation. Another important point of doing research on site in South Africa is that we have to build capacity for HIV and TB there. Africa, despite having a high burden of disease, is lacking in terms of scientific capacity! The funding of Max Planck has enabled me to build more capacity for HIV and TB research on the ground in Africa. This part of my work could not have been done through someone in Berlin. One has to be on the ground for that.

An important factor was that you also have excellent working conditions in Durban.

Yes, when we got the Max Planck fellowships, we were attached to strong local institutions: the Africa Health Research Institute and the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Being hosted by them, I had the necessary support. This allowed us to develop longitudinal follow-up cohorts and we had the infrastructure to generate the insights we are talking about now. In fact, I have been able to visit my patients regularly. The clinic is based in our neighbourhood.

What drives you in your research? What are your goals?

I would like to make a difference in public health in Africa. It’s the people who are most important and they are the reason that we do the work we do. HIV has a huge social economic impact in Africa, and I would like to see things get better. I strive to develop a vaccine to prevent new HIV infections. The other thing that drives me is that I would like to see outstanding research coming out of Africa. Until now, Africa has been kind of a recipient of research. We don't hear of huge scientific discoveries or drugs or vaccines being developed in Africa. And that's a shame for me. We need to change that.

You yourself come from Kenya. How did you first get in contact with the Max Planck Society?

I did my PhD in the US at Harvard University and then came back to Botswana, where I worked in a newly established laboratory. After that I took over an associate professorship at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. At the same time, I was offered the position of an investigator at the newly established KwaZulu-Natal Research Institute for TB and HIV. At that point, Stefan Kaufmann, the Director of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, got involved and proposed to establish two Max Planck fellowships based at the new research institute. I applied and got the fellowship.

What have you been able to achieve as a Max Planck Research Group leader that you probably would not have achieved otherwise?

Without the funding of Max Planck, we would probably not have been able to persist in the previously mentioned studies. It was the Max Planck guaranteed, long-term funding that gave me the opportunity to be engaged in this kind of scientific research. Furthermore, the prestige of the worldwide known Max Planck Society has helped me to gain an international profile. It was a platform to attract additional funding and very gifted students.

What’s next?

I'm going to continue here. I'm now the Director for basic and translational science at the Africa Health Research Institute and Professor and Non-Clinical Chair of Infectious Diseases at the University College London. As for my research, we are now going to be testing a cure intervention in people we identified with acute HIV infection that we have put on early treatment. We now seek to translate the knowledge into an intervention that can help people. The people living here trust us, therefore we are in a better position to directly translate findings from basic research into actual interventions.

Would you like to leave us with a wish?

I wish that the Max Planck Society could continue and expand these kinds of initiatives in African and other low income countries. The more we can work together, the more we can make science achieve social good. Having a longer period of stable funding as we received from Max Planck is so important. In order to achieve impact you need time and a critical mass of people thinking in the same way. The further establishment of these kinds of groups would help to tap into the talent that exists on the African continent and other low income countries.

Interview: Myriam Hönig