Sex differentiation in transsexual kelp

A genetically male strain of giant kelp can produce eggs

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen and their collaborators describe a strain of giant kelp that is genetically male, but presents phenotypic features of females. Their findings shed light on the molecular basis of how sexual development is initiated in this species.

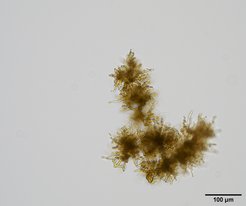

Giant kelp can be male or female, like most animals and many plants. Similar to other brown algae, the reproductive cycle of giant kelp has two distinct stages: the sporophytes are what mostly hits the eye, forming vast underwater forests that are home to many marine organisms. Sporophytes of giant kelp possess both female and male sex chromosomes in each cell, called U and V. It is in the subsequent stage of gametophytes that sex differentiation starts: if these multicellular, albeit much smaller organisms inherit a U chromosome from the sporophyte that produces them, they become females – yellow-green, gold, or brown structure of a round or oval shape. If the gametophytes possess a V chromosome, they develop male characteristics, becoming pale or bluish, filamentous structures. At least that is what scientists believed up to now.

Expression of autosomal genes as a key factor in sexual development

Researchers of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen and their international collaborators were recently able to identify and describe a variant strain of giant kelp with the male V-chromosome – which surprisingly presents as mostly female despite its lack of a U-chromosome. “The genetically male kelp is almost indistinguishable from a female, and most strikingly, can even go through parthenogenesis, a process that usually is exclusive to females,” says Susana Coelho, lead author of the study.

Coelho and her team were able to identify the molecular mechanisms behind this baffling phenomenon. Important for the sexual development are not only the relatively few genes in the U- and V-specific regions, but also other genes – autosomal genes located on chromosomes shared by male and female individuals alike. If and how often these genes are transcribed from the DNA into RNA is crucial for whether a kelp presents as male or female. In the transsexual giant kelp, these gene expression patterns were both feminized and de-masculinized. Analyzing them helped the researchers disentangle what role autosomal genes and U- or V-specific genes play in sexual development. In particular, two V-specific genes were drastically downregulated in the transsexual kelp; one of them had already been suspected previously to play a key role in male sexual development.

Female might not be the “default” sex

However, the reversal to the female developmental program is incomplete: the ‘eggs’ of the genetic male cannot produce the specific pheromone that they would need to attract sperm. Hence, while the giant kelp demonstrates unequivocally that the U-chromosome is not required to initiate the female developmental program, it also showcases its importance: “Previously, we thought that female was the ‘default’ sex in giant kelp and some other brown algae,” stresses Coelho. “But it turns out that without U-specific genes, the kelp cannot produce fully functional eggs – it looks like there is no default sex after all.” Taken together, the results provide the first illustration of how male- and female-specific developmental programs may, at least partially, be uncoupled from sex chromosome identity.