Using walls to navigate the room

Scientists discover a brain circuit that signals the direction and distance of boundaries in the environment to help coordinate next movements

We perceive the world relative to our own body from a self-centered perspective. Yet our brain is able to transform this information into a world-centered, cognitive map of the environment, guiding us independent of where we look or the direction we face. The mechanism behind this has remained unsolved for decades. Now scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research and Goethe University Frankfurt discover a neural circuit in the rodent brain that may play a key role in translating both perspectives and help the animal to detect boundaries to avoid collision.

“Animals use landmarks in the environment as a reference point to identify the self’s position and navigate their surroundings. In rodents, this ability is supported by very specialized types of neurons, including place cells and grid cells, that fire only when the animal is at a precise location in the environment, even in an open arena”, explains Hiroshi Ito, head of the Memory and Navigation Circuits Research Group and the senior author of the new study.

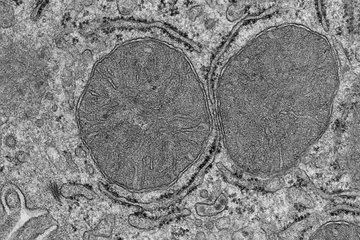

The retrosplenial cortex is an important brain area for processing landmark information. However, the exact function of individual neurons in this brain region is still unknown. “By recording from the retrosplenial cortex in the rat, we discovered a new type of neuron that signals the location of the room’s boundaries such as walls from the animal’s perspective”, says Joeri van Wijngaarden, lead author of the study. “Border cells fire with high precision. In this case, only when the boundary is at a particular distance and direction away from the animal”. But how do border cells know when to be active? Do they use direct sensory cues, such as vision or their whiskers, to detect the walls? To address this question, the researchers manipulated the sensory experience of the animal. “To our big surprise, we saw no difference when the rat explored the maze in complete darkness. The cells kept firing as they did before”, says van Wijngaarden.

Interaction between border cells and spatial cells

Inspired by this unexpected finding, the scientists decided to investigate how border cells interact with spatial cells in a connected brain region, the entorhinal cortex, that is crucial for spatial processing and forming an internal map of the environment. “We recorded activity from spatial cells in the entorhinal cortex while silencing border cells in the retrosplenial cortex with a drug”, van Wijngaarden explains their approach. “At first, we saw no effect. However, when we switched gears and instead silenced spatial cells in the entorhinal cortex, we suddenly noticed a disruption of border cell activity in the retrosplenial cortex”, explains van Wijngaarden. “This was a big surprise as it suggests that border cells capture landmark information without the need to sense it directly. Instead, they rely on spatial information from other brain areas to calculate their position”.

“What struck me most though”, shares van Wijngaarden, “is that there is a close relationship between the activity of these neurons and the animal’s following motion. When the rat approaches a wall to the left, border cells in the right hemisphere are activated, just before the animal turns right. Conversely, border cells in the left hemisphere are active just before left turns, as to avoid collision”. “These findings bring in a whole new perspective to the field. They provide the first insight into how the brain’s internal map can be used to guide our moves during navigation. Hopefully, this will improve our understanding of how the brain makes sense of the world around us in order to get from one place to the next”, concludes Ito.