Master of the tree

Novel form of dendritic inhibition discovered

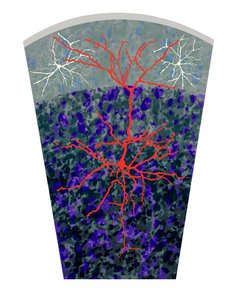

A unique feature that sets neurons apart from all other cells are their beautiful, highly elaborate dendritic trees. These structures have evolved to receive the vast majority of information entering a neuron, which is integrated and processed by virtue of the dendrites’ geometry and active properties. Higher brain functions such as memory, attention and association of information streams all critically rely on dendritic computations, which are in turn controlled by inhibitory synaptic input. In the latest issue of Neuron, an international team of scientists led by Johannes J. Letzkus, Research Group Leader at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, has identified a novel form of inhibition that dominantly controls dendritic function and strongly depends on previous experiences.

Our brain is a remarkably complex system. It is not only comprised of billions of neurons, but each individual neuron by itself even has exceptional processing power. Whether you are trying to find your way around a new city, recalling a past experience or straining to identify a quiet melody, chances are that you achieve these function with the help of distal dendrites on cortical pyramidal neurons, which have formidable computational and plasticity capacities in their own right.

To understand the forces that control these dendritic functions, researchers in the Letzkus lab went in search of a molecular marker for candidate inhibitory neurons. ‘Marker genes and the transgenic animals they enable have become vital tools in circuit neuroscience’ says Johannes Letzkus. ‘They serve as an address in our experiments, enabling us to target a specific neuron type with an array of different questions and methods’. A collaboration with the group of Ivo Spiegel from the Weizmann Institute (Israel) led to the discovery of the first selective marker for inhibitory interneurons in layer 1 of neocortex. Letzkus remembers: ‘We were struck by the extraordinary selectivity of this marker. Even better, in separate work we found that the same gene is also highly selective for layer 1 interneurons in human neocortex, so it will likely also be useful for translating our insights from mice to our own brain’.

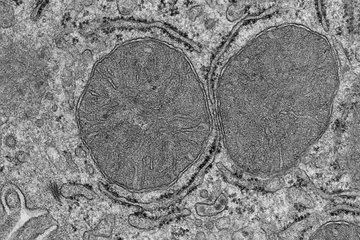

Fuelled by this discovery, the Letzkus lab discovered that these layer 1 interneurons contact many elements in the local circuit, and in particular provide strong inhibition to pyramidal neuron dendrites that are located right next to them. What is striking about this input compared to previous work on other interneurons is that it affects dendritic function at much longer timescales, due to the slower receptors that mediate the signal. Letzkus: ‘Seeing these results made us realize that dendritic trees are controlled by (at least) two forms of inhibition with very different characteristics. What’s more, these two forces don’t merely coexist but in fact interact quite prominently. Thus, one form of dendritic inhibition is successively being replaced when the second one activates, illustrating that this control is very tightly regulated and dependent on what the animal currently needs to compute’.

Which signals recruit these two forms of inhibition? Using an approach pioneered by the Conzelmann lab at the Ludwig Maximilian University (Munich) enabled the researchers to determine the sources of input to layer 1 interneurons throughout the entire brain. Strikingly, these cells receive information from a much greater number of brain areas than deeper layer interneurons, and in particular from more areas that encode the particular relevance of a stimulus. ‘One major reason why we have evolved such sophisticated brains is that they allow us to determine which of the things going on around us at each moment might become important to us’ says Letzkus. ‘When we went on to systematically modify the relevance of a stimulus to the animals in our experiments, we found a striking correspondence with the activity of these interneurons. We have yet to fully understand how this makes the brain better at processing relevant information, but what these data clearly demonstrate is that layer 1 interneurons are critically involved in this process’.

‘Our hope is that the present findings have put these underappreciated interneurons on the map also for other labs. A great feature of the transgenic tools we generated is that they can easily be shared with fellow scientists around the world, enabling concerted progress on these fascinating cells that crown over neocortex’ concludes Letzkus.

JJL/AV