Cuddle hormone relieves pain

Max Planck researchers discover a new effect of oxytocin

Sometimes small molecules are enough to alter our mood or change our metabolism. A prime example is oxytocin, which is involved in fostering emotions such as trust and love. The hormone is produced only in the brain and is released into the bloodstream by the pituitary gland. Until now it was not known why these oxytocin-producing neurons are linked to the brainstem and spinal cord. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg have now discovered a small population of neurons that coordinate the release of oxytocin into the blood and also stimulate cells in the spinal cord. Stimulation of these cells increases oxytocin levels in the body and also has a pain-relieving effect.

Fast birth: the hormone’s name in Greek reflects one of its important functions: During childbirth, oxytocin induces contraction of the uterine muscles and initiates labour. It is also important for forming a strong bond between the mother and child and for stimulating the mother’s milk production. Furthermore, it regulates social interactions in general. It is therefore often referred to as the “cuddle hormone”.

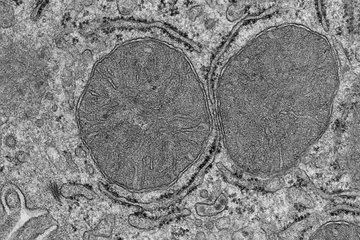

The hormone is produced only in the hypothalamus. Oxytocin-producing neurons are divided into two cell types that differ in size. The larger oxytocin-producing neurons are connected to the pituitary, which releases oxytocin into the bloodstream via capillaries. The smaller cells are connected to the brainstem and deep regions of the spinal cord. The function of these connections was unclear until now. It was suspected that they play a role in controlling the cardiovascular or respiratory system.

Small cells, big effect

Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research and their colleagues from other countries have now discovered a pain-relieving effect of oxytocin and have determined that the hormone’s release is controlled not only via the blood but also via the spinal cord. “We’ve been able to demonstrate a new aspect of oxytocin activity and have also discovered a new subpopulation of small oxytocin-producing neurons,” director Peter Seeburg explains. “A group comprising around 30 cells of the small type extends its nerve endings to the larger neurons, which release oxytocin into the bloodstream via the pituitary and the spinal cord, where oxytocin acts as a neuron-inhibiting neurotransmitter.” This population therefore coordinates oxytocin release. “It’s fascinating that the coordination of oxytocin’s activity depends on so few cells,” Seeburg notes.

By reaching into the optogenetic toolbox, the scientists were able to stimulate the population of small cells in living experimental animals and to release more oxytocin via both pathways. Rats which then had an elevated blood oxytocin level responded less strongly to having an inflamed paw touched, indicating reduced pain sensitivity. By contrast, inhibition of the effects of oxytocin enhances pain sensitivity.

The researchers assume that the human brain also contains the same subgroup of oxytocin-producing cells. “However, the human oxytocin system is probably more complex and consists of more than thirty cells,” Seeburg explains. Moreover, the function of these cells is difficult to investigate in humans. Nevertheless, the findings could provide a new approach for the development of pain therapies.

PH/HR