And the shark, he has teeth...

Form shapes function: Special feature discovered in the enameloid of shark teeth

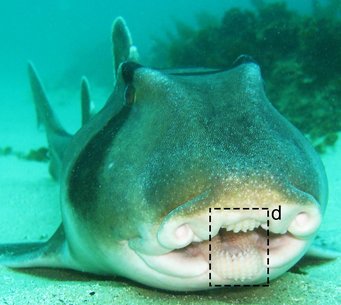

Shark teeth must function to the point during their short retention time: The Port Jackson shark feeds on hard-shelled prey such as sea urchins, starfish, mussels and snails. Its teeth must be able to withstand high mechanical stress. The special structure of the tooth enamel ensures this continuously high performance: "The special feature is that the inner layer of tooth enameloid provides mechanical stability, while the outer one splinters off successively. This allows the tooth to retain its function," says Shahrouz Amini, research group leader at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces. This insight provides new design paradigms for functionalized materials with exterior coatings that can be damaged and replaced, without limiting the performance.

The tooth enamel is the hardest tissue in all vertebrates, as it has to perform a strong mechanical performance and yet remain intact for decades. This is not the case with Port Jackson sharks, whose teeth are regularly renewed. "What is exciting is that all teeth differ in their overall structure, depending on their function, but are similar in their mineral composition," says Peter Fratzl. Apatite is a naturally hard, but quite brittle material. The difference between teeth of other vertebrates and, for example, Port Jackson sharks is the unusually graded structure of the outer (enameloid) layer. Although the teeth wear out and are damaged, their function remains the same until they fall out. "In other words, the shark's dental material is sacrificed in favor of functionality," says Shahrouz Amini.

The port Jackson shark feeds on hard-shelled prey such as sea urchins, starfish, mussels and snails. Its teeth must be able to withstand high mechanical stress. The special structure of the tooth enamel ensures this continuously high performance: "The special feature is that the inner layer of tooth enameloid provides mechanical stability, while the outer one splinters off successively. This allows the tooth to retain its function," says Shahrouz Amini, research group leader at the Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces. This insight provides new design paradigms for functionalized materials with exterior coatings that can be damaged and replaced, without limiting the performance.