How Germans see personalization of online services

Representative study on attitudes to artificial intelligence and data collection

Whether we are looking for a restaurant tip, researching health information, or scrolling through social media posts, algorithms use the personal data they gather on us to determine what we are shown online. But how aware are people of the impact algorithms have on their digital environments? And what are their attitudes to personalized online services and data privacy? A team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the University of Bristol has conducted a survey of 1,065 people in Germany to address these questions.

To ensure that our online experience is closely tailored to our interests and preferences, algorithms collect our personal data and analyze our online behavior. The data collected are used to infer sensitive information and to shape our digital environments. The personalized advertising, product recommendations, and search engine results generated by algorithms then impact the decisions we make.

The findings of a representative online survey conducted by the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the University of Bristol show that most Germans are well aware that artificial intelligence is used on the internet. And they accept customization in the contexts of shopping, entertainment, or search engine results. But the survey results also show that internet users are against the personalization of news sources or political campaigning online. Although Germans have serious concerns about data privacy and most of them object to the use of their personal data, many respondents are willing to accept some personalized services. At the same time, only few of them are aware of and make use of available privacy measures.

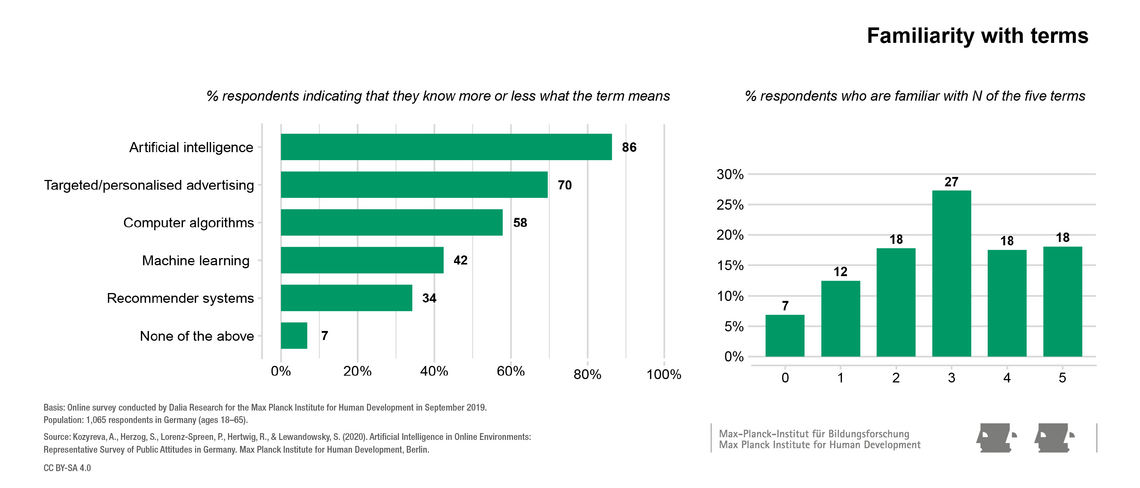

In detail, the survey shows that 86 percent of respondents have a fair idea of what the term “artificial intelligence” means. 70 percent are aware that artificial intelligence is used in smart assistants such as Siri or Alexa. Fewer than 60 percent are aware that artificial intelligence is also used to rank results on search engines and to customize advertising on social media.

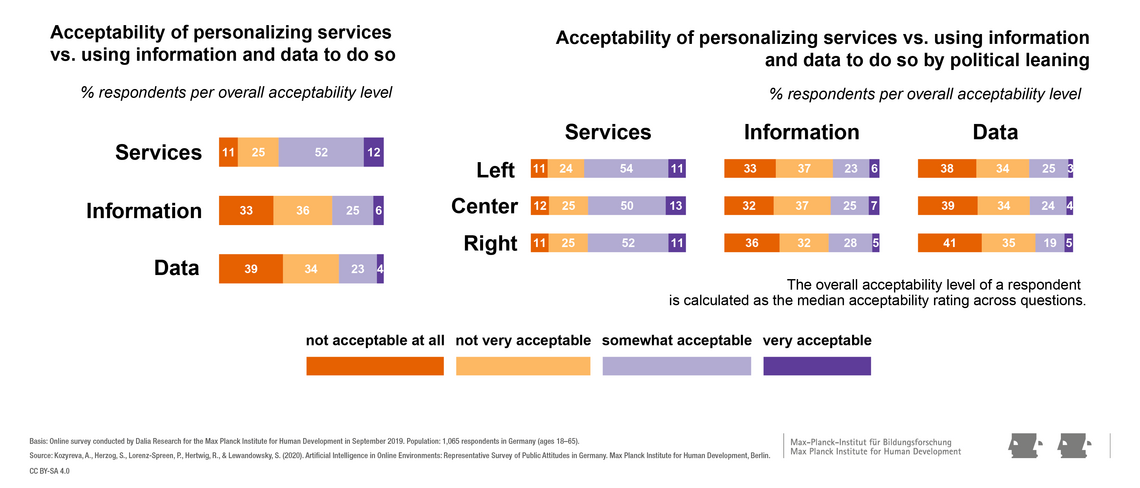

Whether people are aware of and accept the personalization of services depends very much on the content in question. For example, 80 percent consider personalized recommendations of restaurants, movies, or music to be somewhat acceptable or very acceptable. In other contexts, acceptance is much lower: just 39 percent for personalized messages from political campaigns and 43 percent for customized posts in social media feeds.

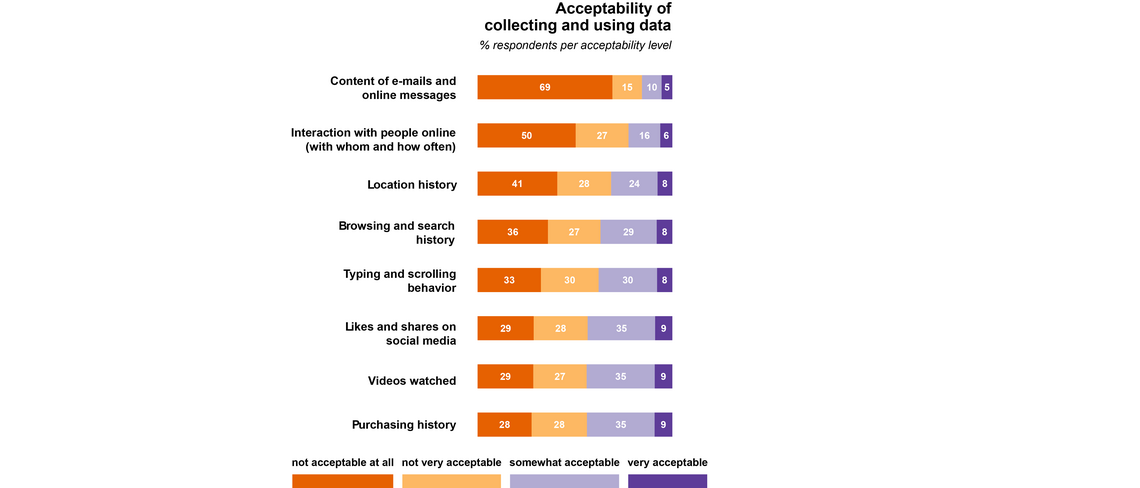

In contrast, there is widespread opposition to the use of sensitive personal information such as sexual orientation, religious views, or personal events for purposes of personalization. Only age and gender information is considered fair game by most respondents (59 percent and 64 percent, respectively). Similarly, over 80 percentof respondents disagree with web services and applications using the content of e-mails and online messages to personalize online interactions.

“There is a clear discrepancy in attitudes here. On the one hand, most people accept customized entertainment recommendations, search results, and advertising. On the other hand, they are unhappy with the data that is currently collected to provide this kind of personalization,” says Stefan Herzog, head of the research area “Boosting Decision Making” at the Center for Adaptive Rationality at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development.

A discrepancy also emerges between German internet users’ attitudes to data privacy and their online behavior. 82 percent of respondents report being very or somewhat concerned about their data privacy on the internet. But only relatively few make changes to protect their privacy online. Just 37 percent report using privacy settings on online platforms. And 20 percent have not engaged with privacy settings or used privacy tools within the past year.

“Despite their concerns about data privacy, few users actually take measures to protect themselves. For that to change, the data privacy functions of online services should be more easily accessible, explained in simpler terms, and made easier to use,” says Anastasia Kozyreva, researcher at the Center for Adaptive Rationality at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development.

Respondents across the political spectrum agree on which customized services are acceptable and which are not. The same applies to the collection and use of sensitive information. Most people share similar levels of concern about data privacy. “It is very interesting that we don’t see any political polarization in attitudes towards personalization and privacy. Policies aimed at protecting online privacy and regulating personalization would meet with broad approval independent of users’ political leanings,” says Stephan Lewandowsky, Professor of Cognitive Science at the University of Bristol.