Time measurements with philosophical significance

Work at the Max-Planck-RIKEN-PTB-Center for Time, Constants and Fundamental Symmetries focuses on very small dimensions and yet deals with some very big questions. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg and the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics in Garching, as well as the RIKEN Research Institute in Tokyo and the Physikalisch-Technische-Bundesanstalt (PTB) Garching, hope to use these insights to develop, among other things, clocks that run more accurately than today’s atomic clocks, which are already accurate to 18 decimal places. The official opening ceremony for the new research centre was held in Tokyo on 8 April 2019.

Work at the Max-Planck-RIKEN-PTB-Center for Time, Constants and Fundamental Symmetries focuses on very small dimensions and yet deals with some very big questions. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg and the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics in Garching, as well as the RIKEN Research Institute in Tokyo and the Physikalisch-Technische-Bundesanstalt (PTB) Garching, hope to use these insights to develop, among other things, clocks that run more accurately than today’s atomic clocks, which are already accurate to 18 decimal places. The official opening ceremony for the new research centre was held in Tokyo on 8 April 2019.

The new clocks will help researchers determine physical constants such as the mass of the electron more accurately, because this process ultimately relies on the extremely precise measurement of frequencies, or rather times. The scientists associate the more accurate determination of physical constants with the question of whether the constants are actually constant. If they aren’t, physicists will need to develop entirely new models to describe the elementary physical relationships that underpin our understanding of the world. Indeed, this would reveal another failing in the Standard Model of elementary particles, which explains the relationships between elementary particles and fundamental forces. Physicists already know that the model does not account for the mass of the neutrino and cannot explain dark matter, which makes up a large part of the matter in the universe.

Why is there something instead of nothing?

By taking precise measurements of time, the physicists at the centre will also research matter-antimatter symmetry. As part of this, they will be looking for differences between particles such as protons and their antiparticles, however tiny they may be. This is linked to a question with philosophical significance: why is there something instead of nothing? With their analyses, the researchers want to solve the riddle of why, although the aftermath of the Big Bang saw matter and antimatter created in equal proportions, the latter has now – to the best of physicists’ knowledge – almost entirely disappeared from the universe. This observation is also incapable of explanation by the Standard Model, which states that particles and antiparticles annihilate when they come into contact with one another. However, the fact that matter – and therefore the universe – exists in the form we know it means there must be an asymmetry between the two.

Apart from answers to fundamental questions of physics, the research at the Max-Planck-RIKEN-PTB-Center could also have some very practical benefits. Specifically, more accurate clocks would allow the development of more precise satellite navigation systems. In addition, time measurements such as these could be used to make a detailed record of the Earth’s magnetic field – so detailed, in fact, that it could help researchers create a density map of the Earth. Given that the local density of the Earth depends on its composition in that location, this would also provide a way of detecting raw materials, such as deposits of oil.

PM

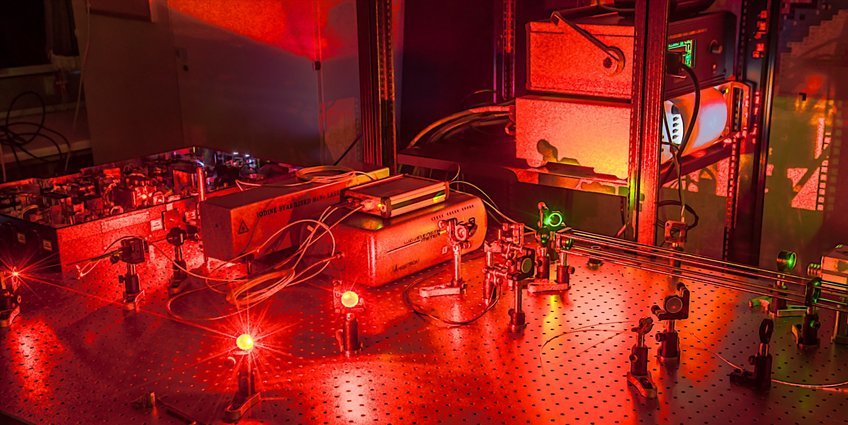

Image: A Penning trap that physicists use to determine the properties of extremely small particles.

Photo: GSI Darmstadt – Gabi Otto