Rapid water formation in diffuse interstellar clouds

Physicists make their first measurements at space temperature

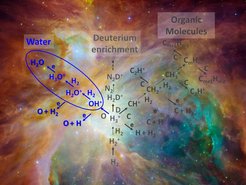

Simplified interstellar chemistry network, showing the gas-phase water formation chain (blue) in front of the Orion nebula.

Accumulations of gas and dust in space can be observed with telescopes as interstellar clouds. Despite the low temperatures and densities, a rich variety of molecules has been found in these environments. The backbone of the cold interstellar chemistry is a network of reactions between charged and uncharged atoms or molecules, so-called ion-neutral reactions.

In today´s universe, ion-neutral reactions in the gas phase can lead to the production of complex molecules, from protonated water (H3O+) to organic compounds. When one of the protonated and therefore positively charged molecules encounters an electron, it can be neutralized and usually breaks up into neutral fragments. This process leads to the formation of neutral molecules in space, ranging from water (H2O) to more complex species, like alcohol and other organics.

But how effective are these processes? To answer this question, it is crucial to find out how often a collision between the reaction partners at low temperature actually leads to a chemical reaction, because collisions are rare in the thin medium. To shed light on these processes, laboratory experiments have to be performed under true interstellar conditions. As these conditions are difficult to realize, present astrochemical models are mostly based on data that have been measured at much higher temperatures and densities, and accordingly are only of limited validity.

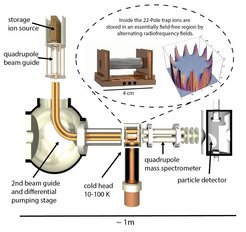

Water forms in diffuse interstellar clouds – where reactions on the surface of interstellar dust play a minor role – via a chain of processes started by cosmic rays. Intermediate products are the hydroxyl ion (OH+) and the water cation (H2O+), which both react with hydrogen molecules, attaching one hydrogen atom and releasing the other one. The ERC-funded ‘Astrolab’ group of Holger Kreckel at the MPI for Nuclear Physics succeeded to measure the reaction rates of these two important steps in the gas-phase formation of interstellar water at low temperatures. The scientists trapped the ions in a cryogenic radiofrequency ion trap, in which temperatures down to 10 degrees above absolute zero are accessible. Up to 100 milliseconds after adding a defined amount of hydrogen gas, they determined how many of the initial ions were still present. From the data, they derived so-called rate coefficients for both reactions, which are a measure of the efficiency of the reactions between the collision partners. It turned out that in both cases practically every collision leads to a chemical reaction.

Overview of the experimental setup, with the cryogenic 22-pole ion trap in the center.

In parallel, colleagues from Cyprus and the USA performed theoretical calculations using a novel method. In an elegant way, this approach employs analogies between quantum systems and the properties of ring-shaped molecules to account for quantum effects which are particularly relevant at low temperatures. The calculated rate coefficients are in excellent agreement with the measured values.

Compared to previous measurements at room temperature, the new values are considerably “faster”. This has implications for the understanding of interstellar chemistry, reaching far beyond the water formation chain. “Our results show once again that it is imperative to use rate coefficients that have been measured under interstellar conditions for astrochemical models“, says Holger Kreckel. “Since this is experimentally often difficult and time-consuming, it is also important to develop theoretical procedures that can cope with quantum effects which are relevant for low-temperature processes, and to benchmark them with measurements. In this case, the strength of our work lies in the combination of experimental and theoretical methods that are appropriate for interstellar conditions.“