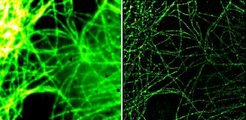

Glowing colours to highlight the minutest details

Max Planck Innovation and Abberior sign licensing agreement for the development of fluorescent dyes for use in high-resolution microscopy

High-tech microscopes are not the only thing needed to obtain crystal clear images from the nanocosmos. Scientists can only make such minute details visible with the help of special fluorescent dyes. Max Planck Innovation, the technology transfer organisation of the Max Planck Society, has signed a licensing agreement with the company Abberior GmbH for the development of such dyes.

Thanks to the development of ingenious new microscopy technologies, scientists are penetrating into ever-smaller worlds and universes. To make processes in cells visible under the microscope, scientists must stain the structures and molecules involved with dyes. These fluorescent dyes are made to glow by light and they emit light in a characteristic wave length. The licensing agreement between Abberior and Max Planck Innovation is intended to advance the development of these dyes. “The agreement with Max Planck Innovation provides the protection rights of the Max Planck Society for the majority of our new dye developments and ensures the exclusivity of these dyes for us,” explains Gerald Donnert, Managing Director of Abberior GmbH.

Abberior is a spin-off of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry and the leading manufacturer of commercially obtainable fluorescent dyes for new microscopy technologies. When developing new fluorescent dyes, the company relies on the expertise of the company’s four founders: Stefan W. Hell, Vladimir Belov, Lars Kastrup and Gerald Donnert. As pioneers in the field of high-resolution microscopy, they have already filed patents for numerous inventions. For example, Stefan Hell, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry was responsible for the development of STED microscopy (Stimulated Emission Depletion). With the help of this new technology, he and his team were able to increase the resolution of light microscopy to 15 nanometres – up to a few years ago, 200 nanometres was still viewed as the theoretical resolution limit. The company’s close contact with basic research means that new developments can quickly be tested in practical applications.

In addition to the STED method, other microscopy concepts now exist that enable researchers to attain very high resolutions. The dyes used must fulfil the special requirements of the individual technologies down to the last detail. With all high-resolution methods, the marker molecules implement a switch between “on” and “off”, which is characteristic for the method in question. Two or more dyes must be tailored to each other here so that multi-coloured high-resolution images can be produced, with which it is possible to mark and visualise different structures.

The demand for such specific fluorescent dyes should continue to grow in the years to come: “High-resolution will be able to replace traditional fluorescence microscopy in many areas in the long term,” says Donnert. The new microscopy technologies have revolutionised the life sciences in recent years. The high-resolution technologies could also become a feature of medical diagnostics in future. Because they provide researchers with completely new insights into cellular processes, they will contribute to considerably improving the diagnosis and treatment of diseases.

MB/HR