Nobel Prize winners in the MPG

The Nobel Prize is considered the highest award in science worldwide. It is awarded annually in the categories of physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature, and peace efforts. The Max Planck Society counts 31 Nobel laureates who were scientific members of the Max Planck Society or its predecessor, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, in the year in which the prize was awarded.

The researchers listed below were not scientific members of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society or the Max Planck Society at the time of the award. However, they conducted an important part of their research in the KWG or MPG or left a lasting mark on it through their commitment to research and administration.

2009 - Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Ada Yonath received the prize together with Venkatraman Ramakrishnan and Thomas A. Steitz “for studies on the structure and function of the ribosome”; it had previously not been possible to study at the atomic level because of its size. She developed a new method to prepare ribosomes so that it would be possible to examine them with the help of X-ray structure analysis. The new knowledge about ribosomes was the basis for understanding the modes of action of antibiotics at the atomic level and thus for developing new antibiotics. Ribosomes are cell organelles that produce proteins for many life processes by reading genetic information from mRNA. She carried out her work at the Weizmann Institute Israel and simultaneously at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin as well as from 1986 to 2004 as head of a Max Planck working group at DESY in Hamburg.

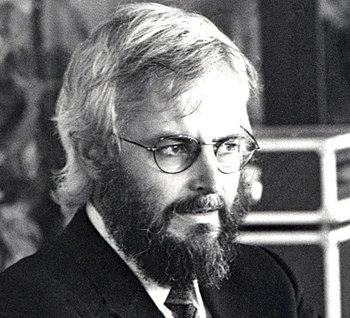

1984 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

Georges Köhler and César Milstein developed a technique for the production of monoclonal antibodies. The Hybridoma technique is still used in many important applications in medicine and science. For instance, monoclonal antibodies are used for active immunisation and for standard tests to determine, for example, blood groups. Köhler and Milstein shared the prize with Niels K. Jerne who was honoured for his “theories concerning the specificity in development and control of the immune system”.

1935 -Nobel Prize in Medicine

Hans Spemann was a pioneer in developmental biology and received the Nobel Prize “for the discovery of the organizer effect in the embryonic stage of development”. Together with Hilde Mangold, he demonstrated that cells in the early stage of germ development in the gastrula are not yet defined for their later development. Spemann recognized that where they are located in the gastrula is the decisive factor for their differentiation. Hans Spemann was appointed Head of Department at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin when it was founded. There, he carried out the transplantation experiments with tissue from the gastrula of amphibians. This ultimately led him to discover the organizer effect. In 1919, he transferred to the University of Freiburg but remained an external scientific member of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology.

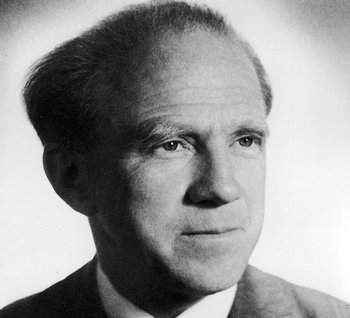

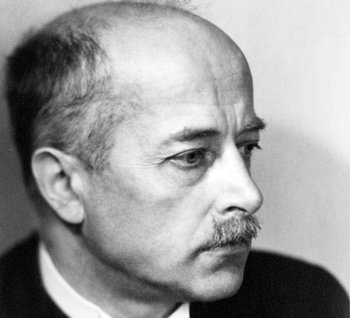

1932 - Nobel Prize in Physics

The Nobel Prize was awarded to Werner Heisenberg “for the foundation of quantum mechanics, the application of which led, among other things, to the discovery of the allotropic forms of hydrogen”. Heisenberg had researched this with Max Born at the University of Göttingen as well as with Niels Bohr in Copenhagen and at the University of Leipzig. From 1942, Heisenberg headed the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin, where he was also head of the German uranium project to harness atomic energy. After the Second World War, he reconstituted his Institute as the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich and made it the nucleus of new lines of research such as astrophysics and plasma physics in the Max Planck Society. Heisenberg thus also left his mark on the West German scientific landscape.

1925 - Nobel Prize in Physics

James Franck received the Nobel Prize in Physics together with Gustav Ludwig Hertz “for the discovery of the laws governing the collision of an electron with an atom”. Both had carried out experiments on this at the University of Berlin from 1912 to 1914. In 1918, Franck moved to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry as Department Head. In 1920, he went to the University of Göttingen as a professor of experimental physics and fled to the USA in 1933 in order to avoid racist persecution. There, he worked in the Manhattan Project on the construction of the atomic bomb, which he then tried to prevent with the “Franck Report”.

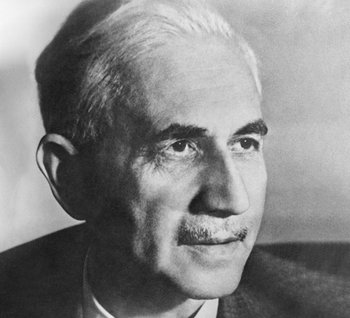

1922 - Nobel Prize in Medicine

Together with Archibald Vivian Hill, Otto Meyerhof received the Nobel Prize “for his discovery of the relationship between oxygen consumption and lactic acid production in muscle”. The work is in the larger context of research on the energy metabolism of cells by Meyerhof and others. This marked the beginning of molecular cell biology. With the identification of ATP and the description of the ATP cycle, Meyerhof had clarified the basic principle for energy-producing reactions in organisms. This has had many far-reaching consequences for medical practice. Despite his Nobel Prize, his home university did not appoint him to a chair – probably because of anti-Semitic resentment. In 1924, he followed the call of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society to its Institute of Biology in Berlin. In 1929, he moved to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, where he spent his most scientifically productive years. In 1938, Meyerhof fled to the US under dramatic circumstances.

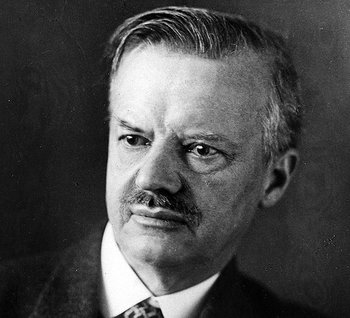

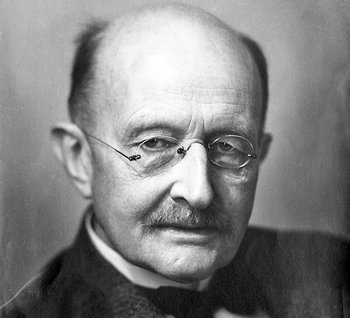

1918 - Nobel Prize in Physics

The prize was awarded to Max Planck “in recognition of the merit he has acquired for the development of physics through his discovery of energy quanta”. As part of his work on thermal radiation, Planck defined the quantum of action “h” in 1900 and thus formulated the revolutionary realization that energy is emitted in quanta. This disproved centuries of doctrine and opened the door to a new era of physics and ultimately quantum mechanics. From 1912, Planck took on important posts and thus helped shape the dynamic development of science in his time. From 1930 to 1937, he was president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. During the Nazi regime, he endeavoured to preserve the autonomy of science. However, he was only partially successful in doing so. In 1945, Max Planck, once again became President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. The western Allies considered dissolving the society but then abandoned their plans. One important argument in favour of retaining this institution was Planck’s personal integrity and his renowned name. Research was continued and rebuilt under democratic auspices as the Max Planck Society.

1914 - Nobel Prize in Physics

He was awarded “for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays as they pass through crystals”, thereby proving the nature of X-rays as electromagnetic waves. He had done the research on this at the University of Munich. As Max Planck’s assistant at the University of Berlin, he had worked on the entropy of interfering radiation bundles as well as on Einstein’s theory of relativity. Max von Laue shaped the further development of modern physics in Germany, among other things by supporting Albert Einstein. He also defended Einstein and his research against anti-Semitic hostility. In 1921, Laue became Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics, replacing Einstein. Laue was critical of the Nazi system. In 1951, he became Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin, which became the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society two years later. During this time, Laue also played a part in making Göttingen an important location for the Max Planck Society and the reconstruction of central physics research institutions such as the National Metrology Institute of Germany.