Ten years of substance research

Centre for the development of new medicinal substances celebrates tenth anniversary

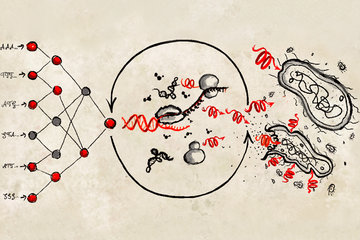

In 2008, the Max Planck Society launched the Lead Discovery Center (LDC) in Dortmund. The organization, which is now independent, picks up on the results of basic research and uses them to develop substances that can then be tested by license or cooperative partners in clinical studies with the aim of establishing whether they are suitable for use in drugs. Ten years after its establishment, the LDC can look back on some impressive results: one of its research projects has managed to make the leap to the clinical stage and is currently being tested in a phase 1b study; two others will be following soon. In all, the LDC has filed 23 patent applications and granted licenses to cooperative partners for research into 15 more substances.

The road from the idea for a new compound to the finished drug is long and full of dead ends. Only one in every ten potential substances tested in clinical studies makes it through to market readiness. For a long time, the pathway from basic research to medicine in Germany was particularly stony. Before the establishment of the LDC, there was insufficient support and expertise for scientists who encountered a novel, medically relevant molecule in their research and wanted to use their discovery as the basis for a drug.

“This didn’t just mean that valuable knowledge went unused. Discoveries of innovative substances had also declined over the years, and the research wellsprings of the companies who carried out little research of their own were running dry,” says Matthias Stein-Gerlach. From 1998 to 2004, the patent and license manager at Max Planck Innovation was the Head of Business Development at Axxima Pharmaceuticals in Martinsried. The start-up was established by cancer researcher Axel Ullrich from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry in Martinsried with the goal of transferring laboratory findings to medicine.

These needs were also noticed at Max Planck Innovation, the Max Planck Society’s knowledge transfer organization. “We noticed that many of the discoveries made by our scientists could not be utilized despite considerable investment in patents. They were simply not yet sufficiently developed for use in the pharmaceutical or biotech industries,” says Stein-Gerlach.

LDC serves as bridge between lab and medicine

In 2006, Stein-Gerlach and Ullrich consequently joined forces with the present-day CEO and scientific director of the LDC, Bert Klebl, to develop a concept for a new research company. This was intended to bridge the previously almost insurmountable chasm between laboratory and industry in Germany. This was a challenge for the Max Planck Society, which is after all especially dedicated to basic research. Moreover, the new centre had to meet the wide variety of needs expressed by the various Max Planck Institutes. Thanks to the strong support provided by the Presidium of the Max Planck Society, the LDC was able to commence operations as early as 2008.

“At that time, only a few people believed that the LDC would be able to look back on such a success story ten years later. The Center has now established itself as an urgently needed link between academic research and the pharmaceutical companies,” says Klebl. The LDC currently employs more than 70 staff members in Dortmund and Munich. It has researched around 70 target and lead structures and issued 15 licenses to industrial partners for purposes of further development; these include Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gruenenthal, Merck and Qurient from Korea. Research alliances have been established with corporations such as AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson and Merck KGgA. “We are particularly delighted that one of our projects has made it to the clinical phase and is currently being tested on patients. Two more are currently in the pre-clinical phase,” explains Michael Hamacher, who is responsible for Finance and Business Development at the LDC.

Nowadays, the LDC stands on its own feet and is open to all scientists. “Researchers from any university or research organization can approach us. We then help them turn their idea into a drug,” says Hamacher. The only snag: demand still far outstrips supply. “We receive far more project-related enquiries than we can cope with. There is accordingly no decline in demand,” says Hamacher.

HR